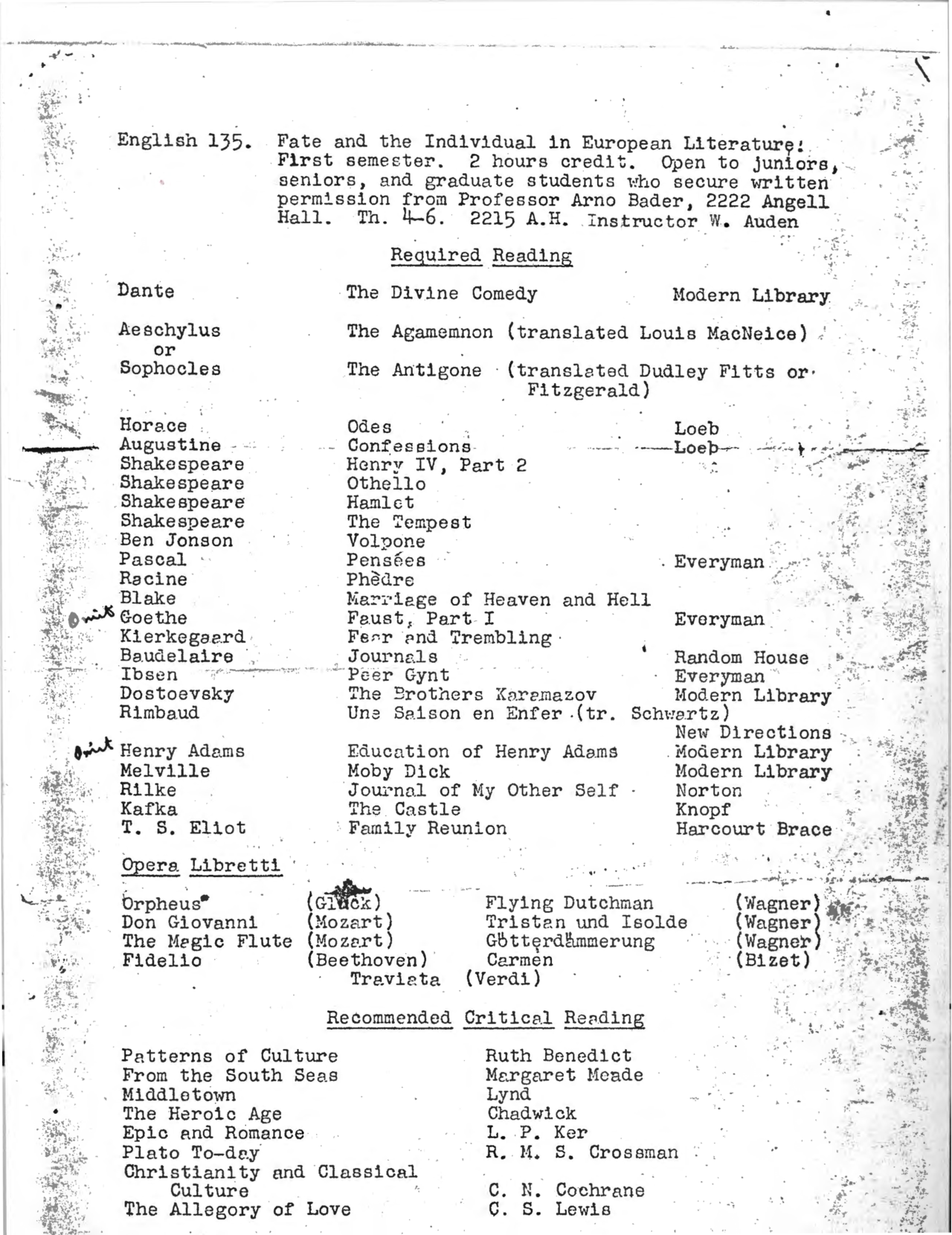

Whether willed, involuntary, or a mix of both, the declining literacy of college students is by now so often lamented that reports of it should no longer come as a surprise. And yet, on some level, they still do: English majors in regional Kansas universities find the opening to Bleak House virtually unintelligible; even students at “highly selective, elite colleges” struggle to read, let alone comprehend, books in their entirety. Things were different in 1941, and very different indeed if you happened to be taking English 135 at the University of Michigan, a class titled “Fate and the Individual in European Literature.” The instructor: a certain W. H. Auden.

In his capacity as an educator, the poet threw down the gauntlet of an “infamously difficult” syllabus, as literary academic and YouTuber Adam Walker explains in his new video above, that “asked undergraduates to read about 6,000 pages of classic literature.”

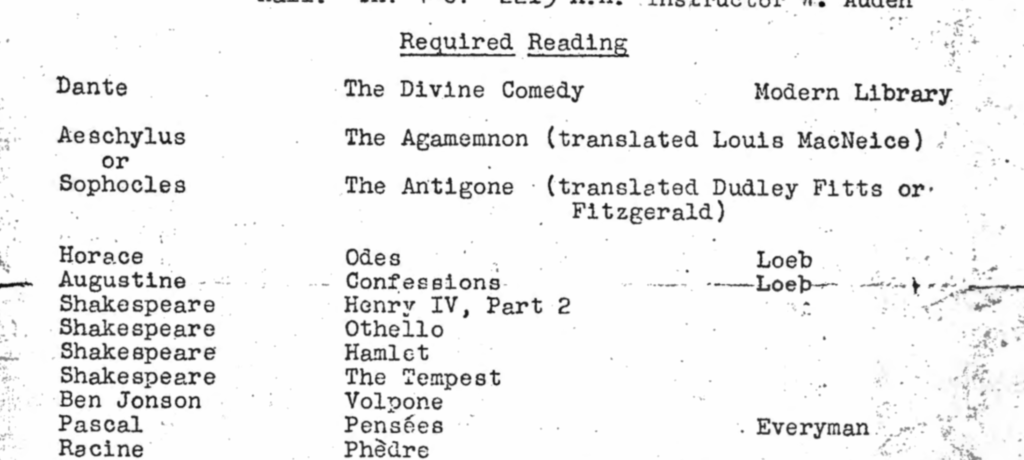

Not that the course was out of touch with current events: in its historical moment, “Nazi Germany had invaded the Soviet Union and expanded into Eastern Europe. Systematic extermination begins with mass shootings, and the machinery of genocide is accelerating. It’s no accident that Auden takes an interest in fate and the individual in European literature” — a theme that, as he frames it, begins with Dante. After the entirety of The Divine Comedy, Auden’s students had their free choice between Aeschylus’ Agamemnon or Sophocles’ Antigone.

From there, the required reading plunged into Horace’s Odes and Augustine’s Confessions, four Shakespeare plays, Pascal’s Pensées, Goethe’s Faust (but only Part I), and Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, to name just a few texts. Not everyone would consider Dostoevsky European, of course, but then, nobody would consider Herman Melville European, which for Auden was hardly a reason to leave Moby-Dick off the syllabus. Walker describes that novel as relevant to the course’s themes of “obsession and cosmic struggle,” evident in all these works and their treatments of “passion and historical forces, and how individuals navigate those forces”: ideas that transcend national and cultural boundaries by definition. Whether they would come across to the kind of twenty-first-century students who’d balk at being assigned even a full-length Auden poem is another question entirely.

View the syllabus in a larger format here.

Related content:

W. H. Auden Recites His 1937 Poem “As I Walked Out One Evening”

Discover Hannah Arendt’s Syllabus for Her 1974 Course on “Thinking”

David Foster Wallace’s 1994 Syllabus: How to Teach Serious Literature with Lightweight Books

Donald Barthelme’s Syllabus Highlights 81 Books Essential for a Literary Education

Carl Sagan’s Syllabus & Final Exam for His Course on Critical Thinking (Cornell, 1986)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Leave a Reply