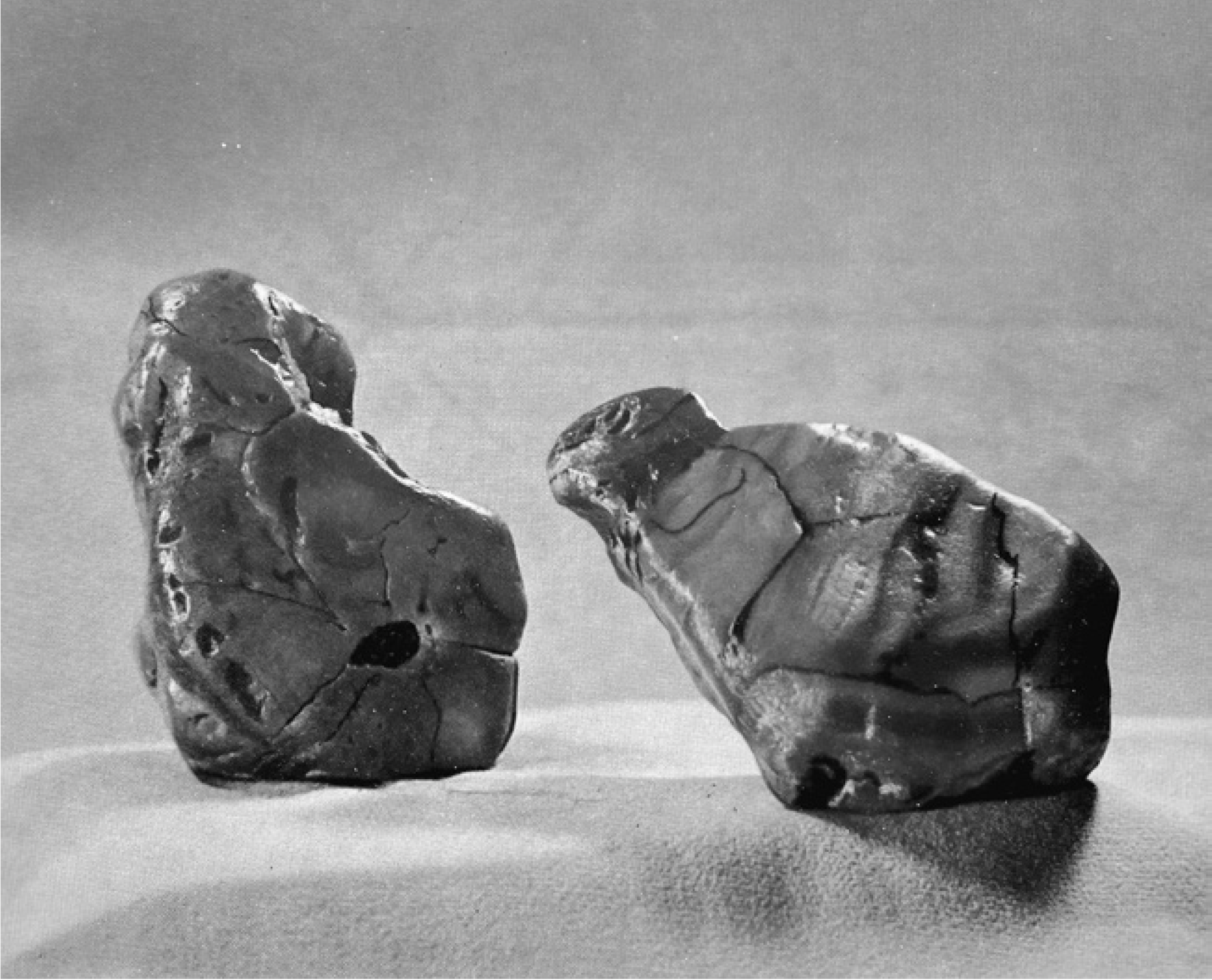

“The Large Tortoiseshell and the Chieftan … discuss the mystery of beginnings and ends.” Photograph by D. Stanimirovitch.

“Infinitely far from the world of flowers,” sighs Novalis. What about the world of stones! And where along the way do we pick up the idea that we know what we’re talking about?

Of course, the question only makes sense to those who believe that nothing around them can be in vain, that everything must somehow concern them; that a perception recurring infinitely from the morning to the night of life, like that of the object generically called stone, could not be purely self-contained and remain a dead letter. The learned classifications of mineralogists leave them entirely unsatisfied. Indeed, these scientists are to them only a category of those “eloquent naturalists” who cling to the visible and tangible and of whom Claude de Saint-Martin could say that “they disappoint our expectation by not satisfying in us this ardent and pressing need, which drives us less toward what we see in sensible objects, than toward what we do not see in them.”1

Without turning to raw gemstones, the mining of which implies traveling to various latitudes and deploying an entire apparatus, nothing is easier than accessing the sense of the special dignity of certain stones. It’s enough to stroll around the Orangerie or along the banks of the Seine, preferably in the sun after a light shower, and let your eyes to drop occasionally and enter the shimmering of flint that carpets the Paris basin like few others. From there, for those who retain the freshness of youth, it would be but a single step to pick up a particularly striking shard and turn it over in your hand to make the light play on it from every side. Indeed, for a child it is an instinctive gesture.

In this way, stones allow the vast majority of human beings who have reached adulthood to pass them by without holding such people up in the least, but those few whom they manage to retain are as a rule never released. Wherever they are found in abundance, they attract these individuals and delight in making of them something like inverted astrologers. The veil of utter satisfaction that had momentarily held their gaze on the stones has gradually lifted; in its place the necessity of a quest is mysteriously imposed on them and grows more demanding by the day. This growing demand leads them to increasingly value, increasingly exclusively, those kinds of inputs that allow them to transcend ever further the almost meaningless idea the average person has of the world. In other words, this way leads into the realm of clues and signs.

Gaffarel,2 librarian of Richelieu and chaplain to Louis XIII, dedicated the name of gamahés (a word, he thought, derived from camaïeu, bastardized from chemaija, which means like the water of God) to stones marked with hieroglyphs, among which he ranks “figured agates” first. Stanislas de Guaïta3 observes that his theory differs little from that of Oswald Croll who, in his Book of Signatures, argues that such imprints “are the signatures of elemental Forces manifesting in the three lower kingdoms” and that, long before them, Paracelsus had studied gamahés at length, attributing healing powers to them. This opinion prevailed in scholarly circles of the seventeenth century, a fact to which this quote from a Prussian author4 attests: “Sometimes it just so happens that beams of light fallen from stars (provided they are of the same nature) unite with metals, stones, and minerals, which have fallen from their highest position, penetrate them entirely, and form an amalgam. It is from this union that the gamahés issue: they are permeated with this influence and receive nature’s signature.” Monsieur Jurgis Baltrusaitis, in a beautiful recent work,5 where one of its three chapters concerns “pictured stones,” recalls that the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher6 believed he could lay out the nomenclature of the different types of minerals that concern us and discuss the causes of their anomalies, which could only be authorized, of course, by divine “Providence.”

In defense of the observers and researchers of the past, it can rightly be argued that organic fossil forms were not recognized as such until the efforts of Bernard Palissy: that we mistook these for the fortuitous figurations which interest us could only multiply the sources of confusion. Camille Flammarion7 emphasizes the fact that despite Steno’s declarations in 1669, “Fontenelle, Buffon, Voltaire remain unsure as to the nature of fossils and do not surmise the mode of sedimentary terrain formation.”

Removed from the long and abusive interference of fossils, it is striking that the empire of the gamahés has lost none of its prestige in certain eyes. Indeed, art has never felt the need to graft itself onto fortuity so much as it does today (look no further than “frottage,” “fumage,” “coulage,” “soufflage,” and other modes of chance composition in painting). Deep down, taste has not evolved much since 1628, when Archduke Leopold of Austria awaited a piece of furniture from Tuscany “draped with agates, carnelians, chalcedonies, jaspers with miniature paintings executed in oil” (ars und natura mit ain ander spielen).8

It’s quite another thing, I can never stress this enough, to manifest a curiosity for unusual stones, as beautiful as they may be, but about whose discovery we had not an inkling, and to fall prey to the search, bolstered now and then by the finding of such stones, even if those that came before objectively eclipse them. It’s as if our destiny is somehow at stake. We abandon ourselves to desire, to the entreaty thanks only to which the object in question can exalt itself in our eyes. Between it and us, as if by osmosis, a series of mysterious exchanges will rapidly unfold, via analogy.

The old miner, known as the “Treasure Seeker,” whom Heinrich von Ofterdingen meets, speaking of the riches that the mountains of the North have revealed to him, declares that he sometimes believed himself to be in a magic garden. I’ve had the same feeling on a beach in Gaspésie, where the sea tossed out and often reclaimed before one could reach them, ribboned and transparent stones of all colors, which glowed from afar like so many small lamps. Last year, as we approached under a light rain a bed of stones we had yet to explore along the Lot River, the suddenness with which several agates of a beauty unexpected for the region “jumped out at us,” persuaded me that with each step, ever more beautiful ones were soon to reveal themselves, wrapping me for more than a minute in the perfect illusion of treading the ground of heaven on earth. There’s no doubt that the persistence in pursuing glimmers and signs, which the “visionary mineralogy” discusses, acts upon the mind like a narcotic. There are even minds that seem ill-equipped to resist it, certain “gamahists” whose work gives them every license to live in their own little world. J.-A. Lecompte9 believes that “fear or violent impressions, religious or political fanaticism, can provoke the spontaneous creation of a gamahé”; J.-V. Monbarlet,10 after many years of “studies,” takes for granted that in the entire Dordogne valley, there is not a single pebble, a single flint that has not been sculpted, engraved, and painted by man—the Gallic artist, according to him—in such a way as to present both without and within (as a crack occasionally reveals) “mysterious pictures” in countless combinations. These two authors believe they should corroborate their thesis with numerous drawings or photographs which, of course, could do nothing but convince us of their “paranoid” cast of mind.

It’s only from the moment such ambitious systematic constructions are erected that, in my view, the rights of visionary mineralogy are overstepped. Among the alluvial stones of a river like the Lot—to stick to what I know best—I’ve often thought those that, during a group search, assign themselves, by their qualities of substance or structure, to each individual’s attention, are those that offer the maximum affinity to their particular constitution. It seems certain to me that, on the same walk, two beings, unless they resemble each other in some strange sense, could not possibly pick up the same stones, so true is it that we find only what meets a deep need, even if such a need could solely be satisfied in a completely symbolic way.

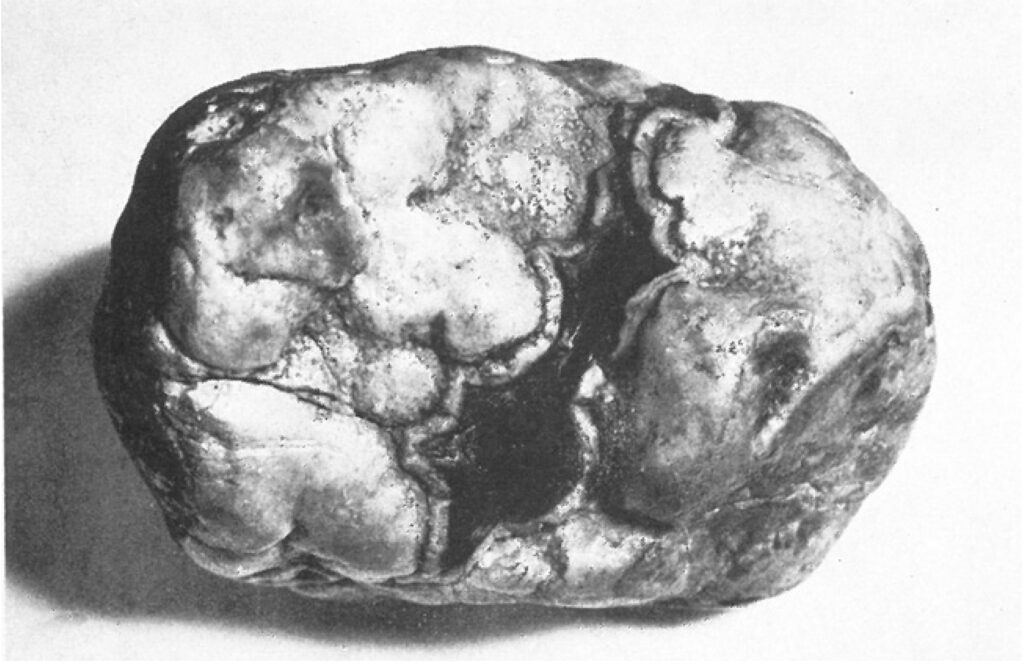

“Every transparent body,” judges Novalis,11 “is in a higher state, and seems to have a kind of consciousness.” I couldn’t have said it better myself. In passing, he leans on Ritter, who, completely occupied with scrutinizing the “universal soul as such,” holds that “all external phenomena must become explicable as symbols and ultimate results of internal phenomena” and that “the imperfection of the one must become the organ revealing the others.” Some of us still react in this way. Internal ribbons of agate, with their constrictions followed by sudden deviations suggesting knots here and there, seem to reflect our own “nervous impulses” in an elective space from the moment we first lay eyes on them. This can result in the most disconcerting “telescoping,”12 for which I can offer no better example than by reproducing here a stone where the woman’s sex, superbly described, opens between swirls of the brain.

“… a stone where the woman’s sex, superbly described, opens between swirls of the brain.” Photograph by D. Stanimirovitch.

The search for stones with this peculiar allusive power, provided it’s a truly passionate one, leads those who indulge in it to fall rapidly into a trance, the essential characteristic of which is hyperlucidity. Setting out from the interpretation of an exceptionally interesting stone, this quickly encompasses and illuminates the circumstances of its discovery. It tends to promote a magical causality assuming the necessary intervention of natural factors with no logical relation to what’s at stake, thereby disconcerting and confounding habits of thought, but nonetheless overpowering our minds.

Last summer, my friend Nanos Valaoritis13 was kind enough to record for me the observations prompted by the discovery of the very beautiful stone in the shape of a seated figure, reproduced here.

Marie W.,14 when at night, on the small roads of the Causse plateaus, she drove us back from the “beaches” of the Lot where we’d lingered, never failing to stop, for fear of killing or hurting it, when a nighthawk, dazzled by the headlights, froze in front of us. Thus, on September 14, we counted nine stops, caused by as many birds, apparently of the same species. The planet Mars, which the newspapers report is exceptionally close to Earth, holds our attention for the better part of the journey.

Again on the fifteenth, with A.B., exploring a small beach near Arcambal. I find a few steps away, in the river, the stone in the shape of a seated figure, whose nighthawk head looks at me. While we’re examining it, the “grand Mars changeant” or “purple emperor,” a relatively rare, always fascinating butterfly, starts fluttering around us. It insistently lands on the dog accompanying us. Another stone, which I discover, resembles even more strikingly the owls of the night before.

On September 17 Mars will be closest to Earth.

A few days later, I learned of a study by A. Lemozi, about a Neolithic burial recently discovered in Tour-de-Faure (Lot). The stone that covers this burial would feature an owl head, which prompts the author to conclude that the Neolithic people of the region worshiped a goddess with an owl’s head, a tutelary deity of tombs. Right or wrong, the more we considered it, the more the stone I found seemed to be a depiction of this goddess.

“… the more the stone I found seemed to be a depiction of this goddess.” —Nanos Valaoritis. Photograph by D. Stanimirovitch.

Such a stone, whose intentional aspect is taken so far, indeed poses a seemingly insoluble problem. As it stands, due to the ambiguity of its origin, it holds for me the immense prestige of the hesitation into which it throws us, which tends to confer on it a key position between the “whim of nature” and the work of art.

Lotus de Païni15 argues that the phase of Intuition historically opens to the human species from the moment “where the soul penetrates to the bottom of the stone and definitively acquires the powers of the SELF. The stone,” she adds, “gave to the human race the high privilege of pain and dignity.” In any case, it seems beyond doubt that only by conceding some of his most precious faculties has man come to consider stones as junk. Stones—especially hard stones—continue to speak to those with ears to hear them. To such people, they speak a language tailor-made for them: by way of what they know, stones instruct people in what they aspire to learn. There are also stones that seem to call for each other; once brought together, one can catch them talking among themselves. In such cases, their dialogue has the immense benefit of lifting us out of our condition by casting the very essence of the immemorial and the indestructible into the mold of our own speculations (the road workers will not suffice). It is, in my opinion, from this angle that for our greater or lesser edification—it is entirely up to us—it is worth observing the Large Tortoiseshell and the Chieftain as they discuss the mystery of beginnings and ends.

Originally published in Le Surréalisme, même, No. 3, Fall 1957.

1 Le Crocodile, 1799.

2 Curiosités inouïes sur la sculpture talismanique des Persans, 1637.

3 Le Temple de Satan, 1891.

4 Johannis Grasset, Physica naturalis rotunda visionis chemicœ cabalisticæ, in “Theatrum chemicum,” 1661.

5 Olivier Perrin, Aberrations, légendes des forms, 1957.

6 Mundus subterraneus, 1664.

7 Le Monde avant la création de l’homme, 1896.

8 Cf. J. Baltrusaitis, op. cit.

9 Les Gamahés et leurs origines, 1905.

10 Le Secret de pierres, 1892.

11 Journal intime, trans. G. Claretie, 1927. Translator’s note: Novalis’s “transparent body” is not literally see-through, but metaphorically refers to a heightened state of matter that reveals inner truth or “consciousness.” For the Romantics and the Surrealists after them, these bodies (such as stones) symbolically bridge the seen and unseen, physical form and spiritual meaning.

12 Translator’s note: Breton seems to be using “telescoping” to suggest reading an image into an accidental, naturally occurring feature, analogous to finding images in da Vinci’s hypothetical stained wall, rather than in its cognitive psychological sense.

13 Translator’s note: Nanos Valaoritis (1921–2019) was a Greek poet and postwar member of the Paris Surrealist Group.

14 Translator’s note: “Marie W.” refers to Marie Wilson (1922–2017), an American artist who was a postwar member of the Paris Surrealist Group and married to Nanos Valaoritis. Breton included her art in his collection.

15 Pierre “volonté,” 1932.

An adapted excerpt from Cavalier Perspective, Last Essays 1952–1966, translated from the French by Austin Carder, to be published by City Lights Books this July.

André Breton (1896–1966) is considered the leader of French Surrealism. Exiled to the United States during the Nazi occupation, Breton would return to Paris in 1945 and continue to lead the movement until his death in 1966.

Austin Carder is the translator of Poetries by Georges Schehadé. He received a B.A. in English from Yale and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Brown.

Leave a Reply