The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefHow a rarely-seen drawing of the Three Graces by Raphael reveals the period’s concepts about nudity, modesty, disgrace – and the artist’s genius. It is a part of an exhibition, Drawing the Italian Renaissance – at The King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace – of drawings from 1450 to 1600, the largest of its type ever proven within the UK.

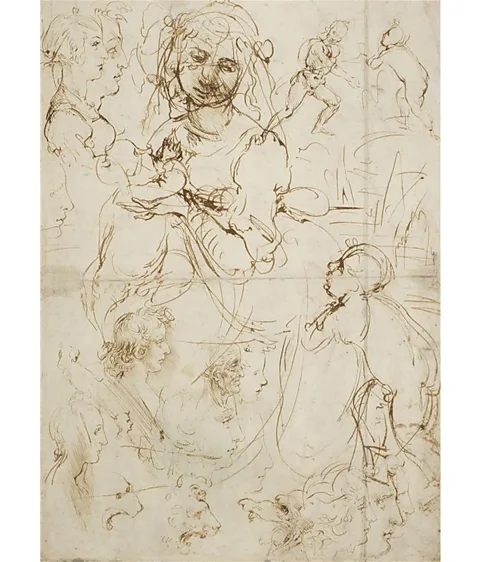

A wandering lobster and a sturdy ostrich characteristic among the many 150 chalk, metalpoint and ink drawings on present at Drawing The Italian Renaissance, on the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. Created by Renaissance giants similar to Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian, usually in preparation for bigger painted tableaux, the works are thought to have entered the Royal Assortment within the seventeenth Century underneath Charles II, a number of as items. For greater than 30 of them, it is their first time ever on public show. Not often proven on account of their fragility, these fascinating drawings – which, on the time, had been starting to be recognised as artworks in their very own proper – make up the broadest exhibition of Italian drawings from 1450 to 1600 ever proven within the UK.

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefRarer nonetheless than these animal research are the drawings of feminine nudes, outnumbered by an element of three by an abundance of bare males. “The male physique is that this absolute focus of creativity,” defined Renaissance historian Maya Corry, discussing the exhibition on BBC Radio 4’s Entrance Row in October. “This can be a Christian society and it is the male physique, not the feminine physique, that is made in God’s picture.” Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, together with his superb physique proportions, is a working example. It’s the male physique, she stated, that “comes closest to divine perfection” in these instances.

There have been sensible points, too. “The artist’s workshop would have been a male setting, and within the absence of ‘skilled fashions’ it will have gone in opposition to all societal norms for a girl to undress in entrance of any man aside from her husband,” Martin Clayton, the exhibition’s curator, tells the BBC. It was male fashions who would pose for Michelangelo, for instance, when he wanted a feminine determine. “This led to misunderstandings and distortions in depictions of the feminine physique.”

Raphael, nonetheless, was among the many first to buck the development, sketching feminine nudes primarily based on actual life fashions. “He was a extremely pragmatic artist, who used drawing brilliantly to deal with visible issues, and to work in a short time from first thought to ultimate composition,” says Clayton. The drawings “enable us to see the artist’s quick responses to the residing determine as they investigated pose, proportion, motion and anatomical element,” he provides. Within the case of Raphael, “his simultaneous decisiveness and openness to variations and prospects is at all times on show.”

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefRaphael’s The Three Graces (c1517-18), a piece in purple chalk with proof of some metalpoint underdrawing, reveals the artist’s genius at work. As he strikes a single mannequin via three completely different poses, we witness the meticulous course of behind creating the exuberant fresco The Wedding ceremony Feast of Cupid and Psyche, the place these three figures will ultimately characteristic, anointing the newlyweds to confer their future happiness. Unclothed, the complexity of the human physique was the last word take a look at of a Renaissance artist’s expertise, whereas additionally satisfying the period’s ardour for science. The ladies’s shapely biceps and quadriceps converse to the identical curiosity in anatomy that we see in Da Vinci’s densely annotated The Muscle tissues of the Leg (c1510-11), additionally on show. However there is a softness concerning the face and stomach that’s lacking from the exhibition’s depictions of males, similar to The Head of a Youth (c1590) with its angular jaw, attributed to Pietro Faccini, or Bartolomeo Passarotti’s sinewy St Jerome (c1580).

The female superb

Very similar to Michelangelo’s David, sculpted a decade earlier, Raphael seems to chase a perfect – even when drawing from life. In a letter reportedly written to his pal Baldassare Castiglione in 1514, he expresses the wrestle of capturing perfection in actual life. “To color one lovely lady I must see a number of beauties,” he writes. “However since each good judgement and delightful ladies are scarce, I make use of a sure concept that involves thoughts.”

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

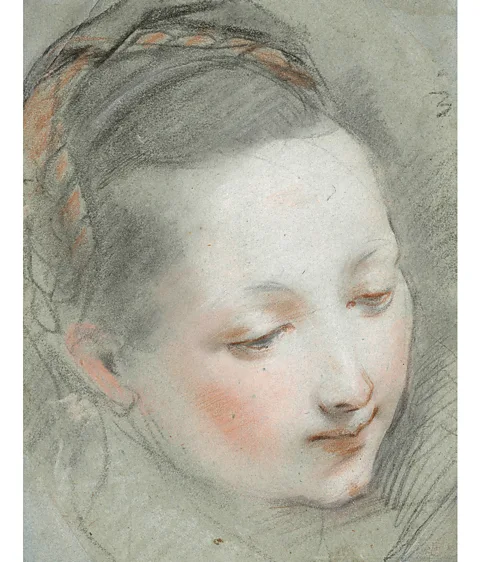

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefIn Raphael’s The Three Graces, “magnificence” means hairless, unblemished pores and skin, and breasts and buttocks as completely spherical because the apples the trio clutch in his c1504-1505 remedy of the parable. When Sandro Botticelli made the Graces a characteristic of his huge tableau Spring, female softness was emphasised by flowing hair and diaphanous materials, whereas Pietro Liberi‘s post-Renaissance rendition of the topic (c1670-80) options the rosy cheeks and marble flesh that we see in works similar to Federico Barocci’s The Head of the Virgin (c1582), painted a century earlier, and likewise on show on the King’s Gallery.

The rarity of feminine painters and patrons within the Renaissance meant that artworks inevitably mirrored the male gaze. “Perceptions of gender and girls’s subordinate function in Renaissance tradition performed out in photographs, and particularly portraits, with photographs of males stressing their social, political or skilled function and standing – the masculine superb being very a lot certainly one of forceful mastery,” says historian and writer Julia Biggs, an knowledgeable in Renaissance artwork historical past. “In contrast, the ladies encountered in portraits from this time are portrayed primarily in relation to the traits of superb (youthful) female magnificence, virtuousness (modesty, humility, obedience) and motherhood.”

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefAs deifications of attraction, magnificence and sweetness, the Graces (Euphrosyne, Aglaea and Thalia), daughters of the Greek God Zeus, replicate a male view of their Renaissance depictions, not simply of what a lady ought to appear like, but in addition of how she ought to behave. They embody this nebulous idea of grace – carefully related to Raphael – which patrons had been eager to connect to their picture. It was a time period that was sure up with distinction, benevolence and love, whereas the Graces’ round dance suggests steadiness and concord − key rules of the Renaissance aesthetic. As a bunch, they mix a patriarchal lesson on female advantage with, unwittingly maybe, a celebration of the feminine type and the sisterhood of feminine bonding.

On the time, feminine nudity had completely different connotations. On the one hand, Biggs tells the BBC, the Three Graces “might have shaped a part of the trope of ‘virtuous nudity’, the place nakedness was “a sign of truthfulness and purity”. Elsewhere, nonetheless, feminine nudity was “related to disgrace”. In Masacchio’s fresco Expulsion from the Backyard of Eden (c1424-27), solely Eve, branded sinful, covers her genitals, whereas Biggs notes that “as a part of the la scopa – the ritual humiliation of adulterous ladies in Ferrara, Italy – ladies had been made to run bare via town”.

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment Belief

The Royal Assortment Enterprises Restricted 2024/ Royal Assortment BeliefSuch feminine nudity contrasted sharply with the modest feminine gown code of Renaissance Italy. “In public, the vast majority of ladies would cowl their our bodies from simply beneath the collarbone all the way down to their ankles, and canopy their arms,” Biggs explains. Mythological and Biblical scenes gave artists a pretext to disrobe them, and likewise answered, says Biggs, the need of male patrons to show “erotic erudition” or maybe even “pay tribute to their very own sexual prowess”. Even when the ladies are dressed, Drawing the Italian Renaissance displays the dichotomous roles obtainable to them, from a seductress in Annibale Carracci’s The Temptation of St Anthony (c1595) to13 completely different Virgin Marys by Michelangelo, Da Vinci and their contemporaries. But, the exhibition means that we do greater than merely stand again and drink within the Renaissance in all its thrives and flaws. Instead of the standard catalogue is an illustrated sketchbook, and drawing supplies are discovered within the galleries. We’re invited to have interaction with the works via our personal artistic endeavour – for some a chance, maybe, to redraw their definition of female and male.

Leave a Reply