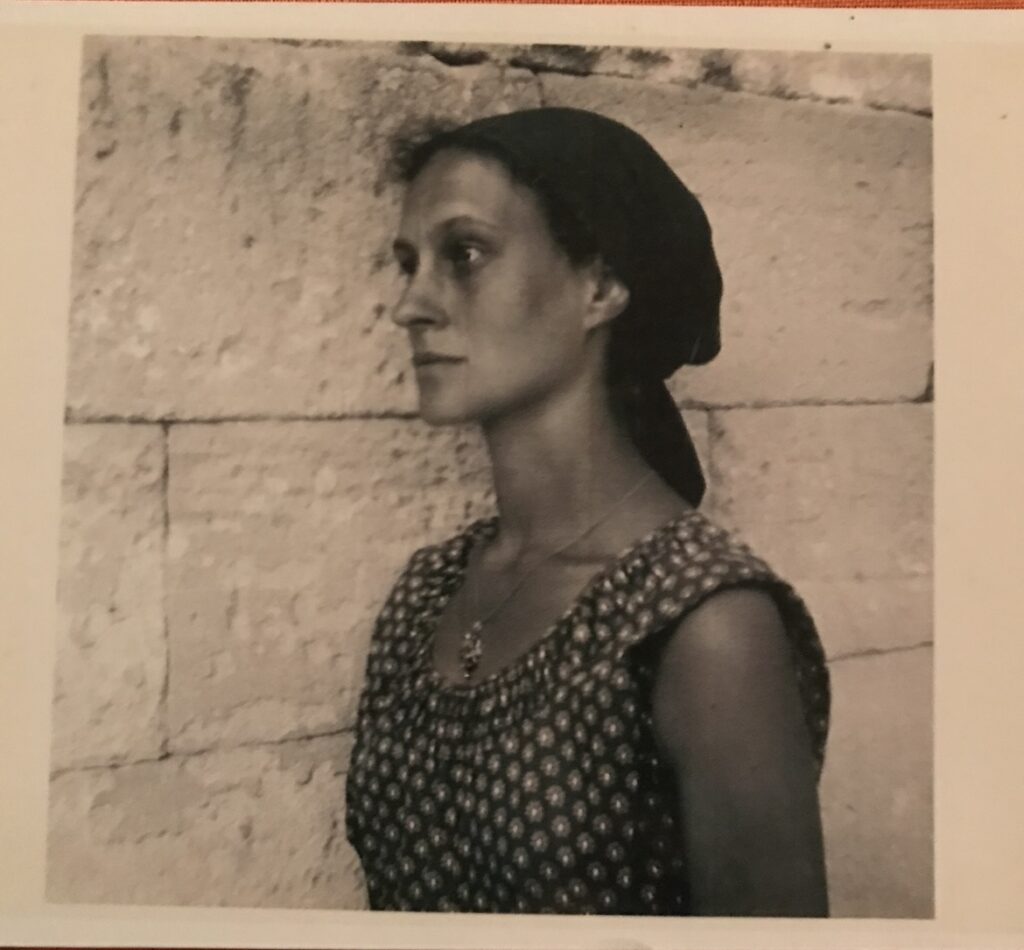

Anya Berger in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Katya Berger.

Anya Berger (1923–2018) is most famous for being the wife and “muse” of art critic and novelist John Berger. In 2018, after both John and Anya Berger were dead, their daughter Katya Berger was with John’s archivist and biographer, Tom Overton, when they unearthed paper records in the family’s basement. These suggest that the work published in John’s name during their relationship, from 1958 to 1973—The Success and Failure of Picasso, Ways of Seeing, G., and A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor—could be considered joint projects. The private family archive documents a period largely missing from John Berger’s main archival holdings at the British Library.

Née Zisserman, Anya Berger was born in Manchuria to a noble Russian father and Viennese Lutheran mother, considered Jewish by the Nazis. She came to England as a refugee in her teens, first on scholarship to St. Paul’s boarding school, and then to read modern languages at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford. She was a polyglot, responsible for shaping the English-speaking left with her translations of Marx, Lenin, fallen Freudian Wilhelm Reich, and architect Le Corbusier.

The collaborative nature of her relationship with John was no secret; they once signed a telegram “jonanya.” Although Anya was the linguist, they worked together “officially” on a few translations, most famously Aimé Césaire’s Return to My Native Land (1939, trans. 1970). Ways of Seeing (1972), the TV show and subsequent book which made John Berger a household name,drew heavily on Walter Benjamin’s writings on art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Anya, a fluent German speaker, had introduced her husband to Benjamin’s ideas before the Arendt-Zorn translation of Illuminations was published in English in 1968.

Anya Berger appears in the second episode of Ways of Seeing, on “Women and Art.” The show presents the concept of the male gaze to a mainstream audience a year before Laura Mulvey would write her canonical essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Part of a roundtable of women tasked with responding to female nudes, Anya is the first to speak, seated across from her husband, leaning forward assertively over her widespread knees. “Of course, weall have an image of ourselves, and it’s a visual image, but I wonder how much this sort of classical, European painting has shaped that image.” She is animated.

“When I look at the paintings that you show in your film, I can’t take them seriously, I cannot identify with them because they are so immensely exaggerated always, they fasten on to some sort of secondary sexual characteristic, these enormous breasts and great big bee sting bottoms [John Berger’s laughter], huge things like that, and they just aren’t real … Nearly all the paintings you have shown are what is called idealized, and therefore they are to me very unreal in connection with any deep down image that I might have of myself, and in connection with any deep down pleasure that I might have in looking at another female body.”

Anya Berger advances and complicates the show’s narrative arc. Her frame of reference is centurial, looking beyond decades and cities to eras and continents. Yet her name only flashes up on the screen during the closing credits for fewer than five seconds. John and Anya were close to breaking up by the time the book from the show was published. It became one of the most widely read art books on record, with sales in the UK alone totaling 1.5 million. It fails to register her contribution.

There was a degree to which she conceptualized her role as that of the muse: her daughter Katya has suggested “mentor” is a better fit. She saw herself participating in the creative work of her lovers, and those in her networks, as both an inspiration and as an interlocutor, shaping the work from the inside. “I wanted to partake of the creative life,” she told her granddaughter Sonia Lambert, “but I knew that I myself was not a creative artist, I didn’t have the wherewithal. I loved partaking of it.” One of the things that began to irk Anya Berger after separating from John, though, was the sense that she had been exploited as part of their creatively collaborative relationship.

In the summer of 1969, John Berger sought to open their marriage to another woman, Annar Cassam. He was writing the novel G., a book about the gradual politicization of a Don Juan figure in a pre-World War One Europe: it would go on to win the Booker Prize the same year that Ways of Seeing was first broadcast. That novel is dedicated to his wife and to her feminist peers: “For Anya/ and for her sisters in Women’s Liberation.”

He was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with his wife’s influence over his writing. Katya spoke to me of how her mother’s support of her father’s work had become so critical that he felt repressed and inhibited. It is significant that his next steady partner, Beverly Bancroft, with her background in the business aspect of publishing, was concerned more with licensing and rights than the content of his work, more agent than collaborator. Anya was unconvinced of John’s vision for the Into Their Labours trilogy, a project that would eventually take him over ten years to complete, and tried to persuade him to put his energy elsewhere.

Katya also remembers the difference in attitude to each of her parents’ literary work in their home. John Berger’s writing time was sacred, and everyone in the house was obliged to be silent. By contrast, Anya Berger wrote only after her many tasks were fulfilled, moments announced by the click and ding of the typewriter. Perhaps it is significant that most of her unpublished archive is fragmentary, or takes the form of diary entries, which can withstand the domestic routine’s many interruptions.

Papers in the private family archive document a period of massive creative productivity for Anya Berger around the time of their separation, spurred on by a kind of bruised exhilaration. Some of this writing found formal outlets: an article called “Women of Algiers” for The New Left Review in 1974, and a piece called “in the shit no more” for the trailblazing British feminist publication Spare Rib in 1976. The latter is billed on the contents page as “The saga of a lone woman and a broken lavatory seat.” She provides an amusing account of her efforts to replace a malfunctioning toilet seat while her two children are home sick, getting shit on her fingers, and the elation that comes from her ultimate success: “My duel with the lavatory seat had been the nearest I’d got to pure sport in 51 years. My very own, private Olympiad.”

There remains a treasure trove of Anya Berger’s unpublished life-writing: journal entries, memoir, poetry, letters, telegrams, doodles, short stories. Katya drew my attention to how the pieces were revised, corrected, and for the most part dated and organized; her mother had carefully archived the work, as if it were intended for readers, possibly eventual publication. In an untitled fragment from the summer of 1974, after her separation from John, she begins: “To live alone is, first and foremost, not to be seen. No interested eye observes you. You project no image. Unless it be to yourself.” This develops, over the course of two pages, into a reflection on her struggle to write, to find a new way to see herself and be seen: “Then a thought came into my head which seemed more interesting than the previous ones. I played with it for a while & was preparing to let it go like its predecessors. But it occurred to me that, possibly for the first time in my life, I was free to think it through—if not to the end, at least to greater depth. That seemed to be what I wanted to do.”

Anya Berger’s writing practice then trailed off for many decades. On her deathbed in 2016, though, when she was slipping in and out of lucidity, speaking to her children in French and in English, she provided detailed outlines of stories that had been circling around in her head, fictionalized versions of people she had encountered and scenes she had witnessed. Some are drawn from her own ongoing private conversation with Katya, about romantic failures and successes, disappointments and hopes. “I am writing a new book in my head,” she said to her daughter, “It is about Katya, an old lady pushed in the sea by her lover.” For Anya Berger, the things that didn’t happen in her life carried all the force of an event.

I am working in collaboration with Katya Berger and the feminist writer Mona Chollet to publish a two-volume collection of Anya Berger’s life writing. The fragment The Paris Review is publishing, “New Optic,” was written in 1969. It’s a personal essay about eyesight and aging, but it touches on a subject, seeing and being seen, which was never far from her mind. “The new way of seeing,” Anya writes, “suddenly became the normal one and the old way—quite tolerable until then—became abnormal and indeed impossible.” Here, three years before John’s TV show aired, she anticipates—gives it?—its title.

Emily Foister researches, writes, and teaches on feminism and women’s work, with a focus on precarious archives.

Leave a Reply