Tetney Tank Farm: aerial 2025 (2) by Simon Tomson, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve contributed to our pages. Millicent Borges Accardi’s “Good Tank Farms” appears in our new Winter issue, no. 254.

How did this poem start?

A teacher, Gay Talese, once advised me to incorporate my day jobs into my writing. At the time, I was working for a dog food manufacturing plant on Malt Avenue in Commerce, California. I’d also worked in oil refineries for ten years or so. I worked at the ARCO Carson refinery as a technical writer from 1992 to 1997, as well as for other refineries and oil-related companies such as BP, ampm, and ARCO Marine (oil tankers). From 1997 to 2016, I was a contractor at Chevron, supporting their refineries from El Segundo, California, to Pascagoula, Mississippi. I had my own safety glasses, hard hat (adorned with worn stickers), and blue fire-retardant Nomex coveralls with my name patch over the pocket. I was familiar with the quirky systems and individuals who make up a ruff-and-ready refinery workplace. I wanted to write about a technical work location in a poetic way—about the serious aspects of blue-collar work, but also its magnificent moments of reflection.

I’ve always admired Fred Voss, and his poetry about being a machinist at an aircraft plant in Long Beach. I wish we had more blue-collar writers these days. Where are the Jack Londons? And the Steinbecks? Where are the writers who work on the dock? Where are stevedores, the longshoremen? The pipe fitters? The electricians?

From Internet Archive

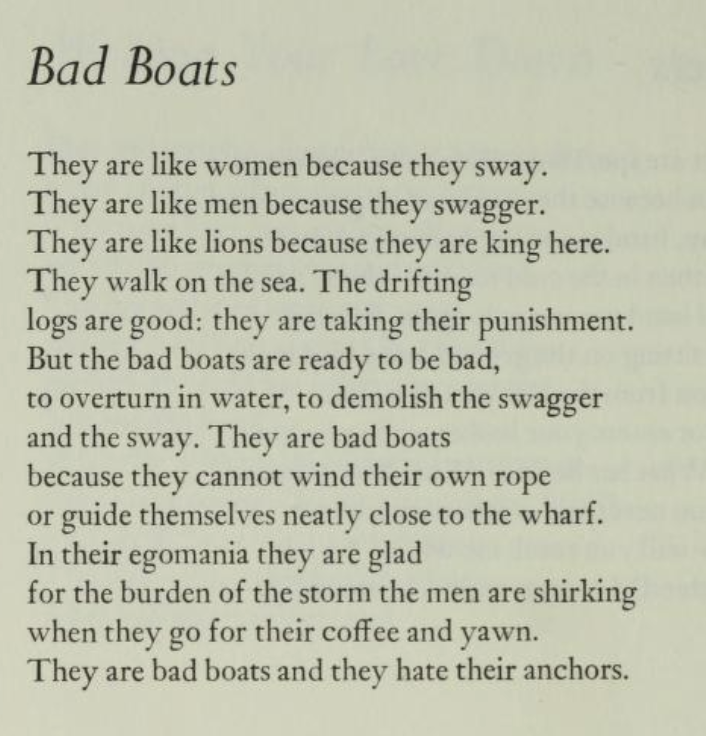

Then, one year ago, the writer Jesse Nathan introduced me to the poem “Bad Boats” by Laura Jensen. I was inspired by her structure and stark imagery, how the poem gets inside a topic and inhabits it in every way, twisting and turning the topic over its hand and allowing the reader to see every angle. I’d already been writing about oil refineries in a series of narrative poems about a refinery old-timer named Larry James—how he approached, or attacked, life, and his unique philosophies. So, wanting to riff on Jensen’s poem, I wrote about “good” tank farms instead of “bad” boats.

What are tank farms?

Tank farms are massive aboveground tanks used for storage in support of the oil refining process. They might contain petroleum by-products for blending, or an overflow of crude or finished-product gasoline, awaiting transport via pipeline or railcars. Tank farms help manage bulk storage and play a key role in the blending of oil products.

They’re peaceful, and apart from the commotion of the rest of the refinery, in their own area, where it is unusually quiet and uninhabited. Still-full. There is a majesty about tank farms. They remind me of the Easter Island statues. Everything in the tank farm is bigger than you are. It is like being in a vast desert where things are still and nothing moves.

No one can enter a tank, but people hang out around them. On the job, being sent to the tank farms was either a blessing or a curse. When two workers get into a spat, it is common to say, “Let’s take this out to the tank farm.” Or, when you need a rest from a double shift or a late night, a well-meaning supervisor might say, “Take the truck and go put your feet up. I’ll come get you later if we need you.”

Tank farms are homey. They’re places to rest or hide out. A couple of guys might go out there in pairs and bullshit about the good old days, because the tank farm always looks the same, whether you started working there two weeks ago or twenty years ago. Sacred like an Indian burial ground, the stories are out there just waiting to be told.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

Another influence was the art of Richard Serra, who creates huge sculptures with rusty, warped, thick iron sheets. I saw some at a show at MOCA in Los Angeles, where you could touch the faces of the heavy sheets and walk through them. In some places they were wide apart, divided, and in other areas they were welded together. The museum was noisy, but everything was quiet inside the sculpture. So silent. No echoes. As hollow as the wind. Being inside these large-scale sculptures made me wonder what it might be like inside a tank: all cylindrical, all hollow, round, and still. Take a tank and turn it inside out, and you would have a Richard Serra artwork.

What was the challenge of this particular poem?

The hardest part about writing is the first hard keystroke, the first pen mark. It starts out slow—click, click—and then before long it is clicky-clicky and groan and a busy array of keyboard sounds. Poems often describe a problem and then offer a solution or resolution. They also hold up a mirror to a moment.

With “Good Tank Farms,” I struggled with how to bring the refinery environment to life without sounding shallow or technical. I wanted to incorporate oil industry terminology and the names of specific sites, like Gate 7, The Slab, and Babikian Way. These are locations at an oil refinery in Carson, California, formerly owned by ARCO and now, I believe, run by Marathon. Babikian Way, for example, is a street on the refinery property named after former ARCO president George Babikian, who worked at the company for some sixty years. As a manager, he was well known for “blowing up” the gas credit card, setting up ampm convenience stores, and selling gas for five cents less than everyone else. He was much loved at the company.

I interviewed many SMEs, or subject matter experts, in the process of writing technical manuals and training materials. Their stories would roll over these holy, ancient, inherited nicknames of places as if they were describing the cheapest way to get from the Upper West Side to Times Square.

What is your editing process like? Do you have drafts of earlier versions of this poem?

I never keep drafts, per se. I go crazy comparing and saving different versions. All having multiple drafts does is instill a lack of confidence in me. Not keeping drafts helps me to be decisive, to make a solid choice. When I have an answer, I make the change. I think of Walt Whitman, who continued to rewrite Leaves of Grass long after it was published. The thought alone gives me nightmares. Why return to the scene of the crime? Why not move forward instead?

When I was in grad school, I lost one of my (at the time) best poems, called “Birth.” So I sat down and tried to rewrite it while it was fresh in my mind. What happened was astonishing—I remembered only the good parts. All the issues I’d been struggling to resolve were mysteriously gone.

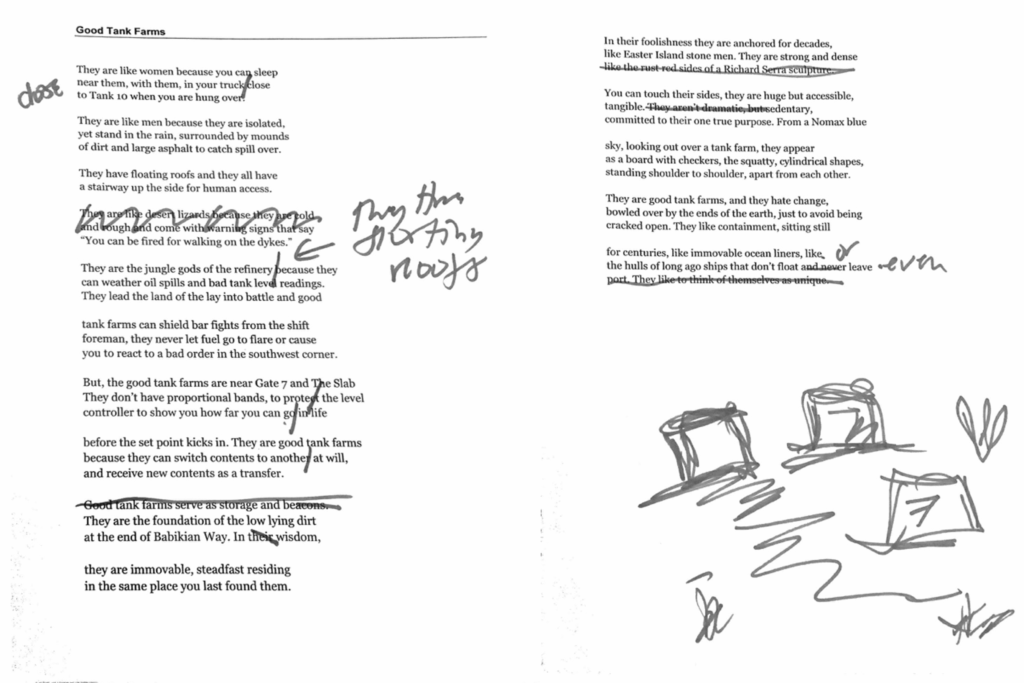

But I was able to find an early version of “Good Tank Farms” in my email. The changes from this version were mainly in the line breaks and moving passages that thwarted the flow.

In the first stanza, I broke the second line on the stronger word truck, rather than on close. I removed two lines in the fourth stanza because they were mere descriptions that did not forward the action of the poem. In the fifth stanza, I broke a line at refinery rather than ending it on because they. Then I inserted “They have floating roofs.” In the seventh stanza, the lines were changed to break at protect and go. And the eighth stanza also has new line breaks, breaking at another rather than the weaker end words at will. In the ninth stanza, I deleted the first line and the word their. In the eleventh stanza, I deleted the last line, and also a passage in the twelfth stanza for clarity. A significant change is in the last stanza, where I deleted the last line entirely and ended the poem with

They like sitting still for centuries,

like immovable ocean liners, like the hulls

of long-ago ships that don’t float or leave ever.

Where did you write this poem? Can you share photos of your workspace, or workspaces?

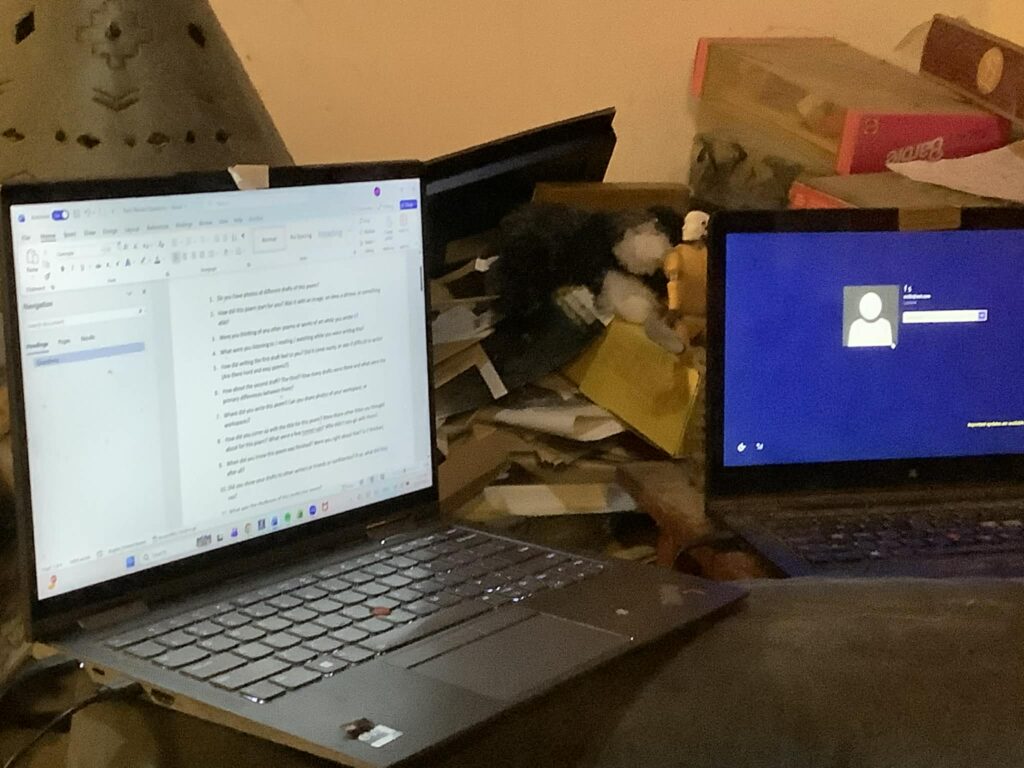

I write in inconvenient places. As I write this, my laptop sits dangerously on the edge of a worn couch armrest, and I am scrunched over it awkwardly. My legs are folded underneath me. A box of Kleenex is on my lap because I am sneezing like crazy from some wind that brings dust in the air, or maybe an errant bobcat (I am allergic). When I am given a perfect office, I draw a blank. I feel pressure to produce, and no words come to me. Where I live now, in Topanga Canyon, I have a desk I never use. Mostly because it faces a bookcase. I’d rather sit on the old blue couch, where I can see the creek through a side window of my hippie shack, and a black walnut tree next to the wooden deck with squirrels and wild birds.

I think the inconvenient nature of my writing locations has its origin in childhood: As an only child, I was dragged along to my parents’ parties and my dad’s job at Sears. I had to occupy myself in the corners of everywhere, reading books or writing in purple notebooks.

So I adapt. At a residency in Spain, I wrote on the veranda with the tiger winds swirling around me. I’d wander into the kitchen and help the cooks make bread and then sit around with them while the loaves were baking, scribbling notes on pieces of paper.

But I get my best ideas when I have no paper or pen around, when I am in an inconvenient spot where it is difficult physically to write. I seem to thrive on adversity and chaos. I like a good mess with scraps of crumpled paper and open books piled up. A clean, well-lit place with fresh pencils in a shiny jar and a comfy leather chair is my nightmare.

Millicent Borges Accardi is the author of four poetry collections, including Only More So.

![Research-Based Factors Of A Highly Effective Learning Environment [Updated]](https://breshlynews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Research-Based-Factors-Of-A-Highly-Effective-Learning-Environment-Updated.png)

Leave a Reply