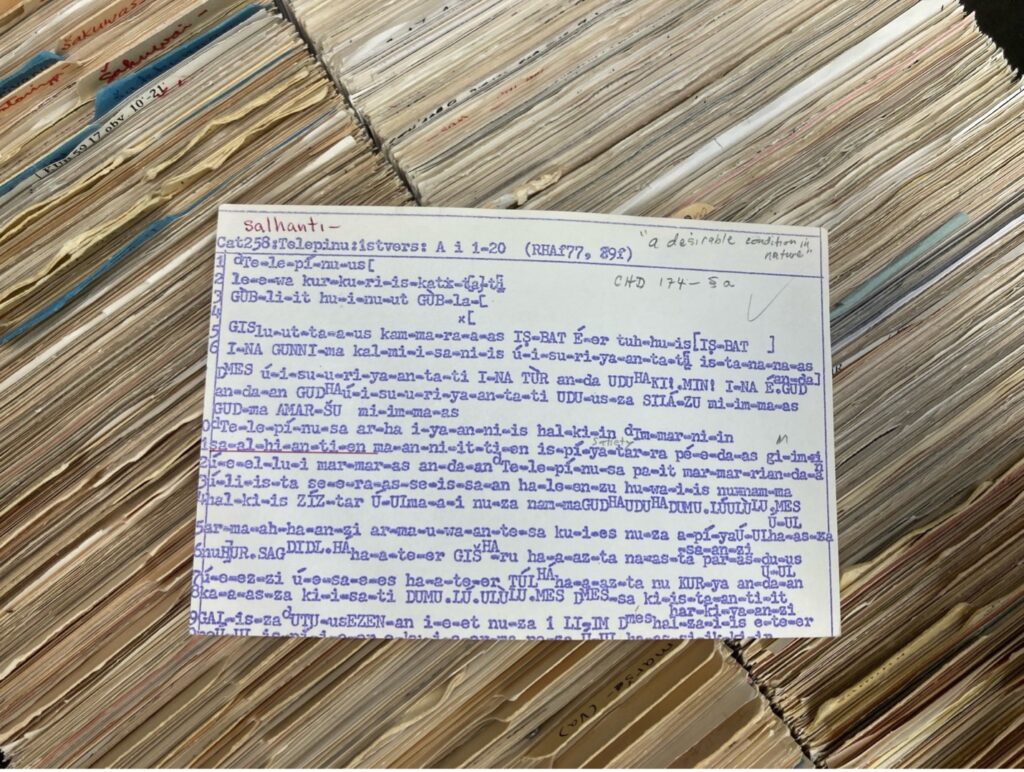

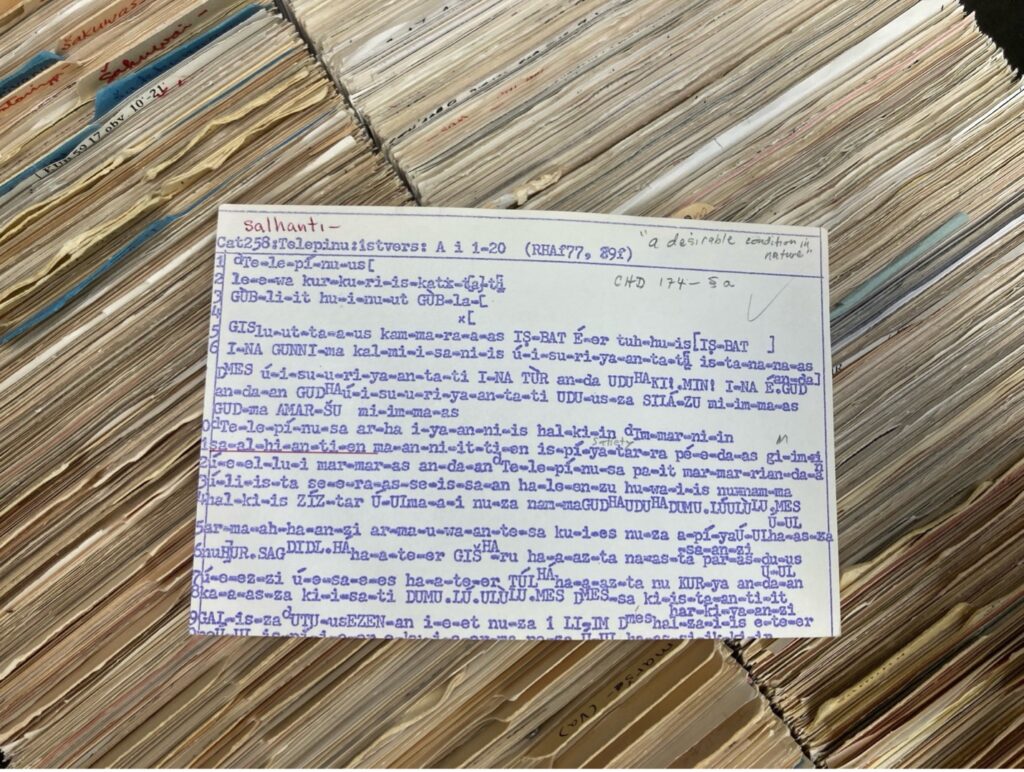

šalḫanti-/šalḫiyanti- lexical filing card, with this paragraph from the Disappearance of Telipinu in the Chicago Hittite Dictionary. Courtesy of the author.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Naomi Harris’s translations of three Hittite poems appear in our new Fall issue, no. 253. Here, we asked Harris to reflect on her translation “Telipinu went.”

The Hittites spoke an Indo-European language and ruled a major empire during the Late Bronze Age, in what is now Turkey. Their capital was multicultural and multilingual. Their language, which we call Hittite, they called Nešili, the language of Neša. “Telipinu went” translates a paragraph from the Hittite text that we call The Disappearance of Telipinu. The text was written in cuneiform script on a clay tablet, found at the Hittite capital Ḫattuša, near modern-day Boğazkale in Çorum, Türkiye. There are several versions, and it was copied again and again over the course of Hittite history; this one dates from about 1450–1350 B.C.

“Telipinu went” is an extract from a longer manuscript. Can you tell us about that?

In the full manuscript, the god Telipinu, son of the Stormgod, becomes angry and leaves, taking all the good things away with him. Famine and disaster ensue in both the mortal and divine realms. The waters, mountains, and woods dry up. Cows no longer recognize their calves. Ewes no longer recognize their lambs. The world is twisted and out of joint. No one can become pregnant, and those who are pregnant cannot give birth. The Sungod throws a party, and although the gods eat and drink as usual, they find that they are still hungry. When the Stormgod realizes that his son has left, the great gods and the small gods search everywhere for Telipinu but do not find him. The Sungod, host of the party, sends a swiftly flying eagle, but the eagle doesn’t find him. The Stormgod makes a pathetic effort to find his son and gives up far too quickly. Finally, the grandmother goddess, Ḫannaḫanna, sends a bee that finds Telipinu and stings him awake. The bee returns Telipinu, and they perform a ritual brimming with exquisite similes to remove his anger and reconcile him with the world again.

The paragraph I focused on, KUB 17.10+ §5’, reads as follows—

dtelipinuš=a arḫa iyanniš

ḫalkin dimmarnin šalḫiantin mannittin išpiyatarr=a pēdaš gimri wēllui marmaraš andan

dtelipinuš=a pait marmarri andan ulišta

šēr=a=šši=ššan ḫalenzu ḫuwaīš

nu namma ḫalkiš ZÍZ-tar UL māi

nu=za namma GU4ḪI.A UDUḪI.A DUMU.LÚ.U19.LUMEŠ UL armaḫḫanzi

armauwanteš=a kuieš

nu=za ape=ia UL ḫaššanziTelipinu went away.

He brought away grain, Prosperity (deified), growth, abundance, and satisfaction; to the field, to the meadow, to the moors.

Telipinu went, and he hid himself in the moor,

and duckweed ran over him.

Afterwards, grain and emmer no longer grow.

Cattle, sheep, and people no longer become pregnant,

and those who are pregnant,

they, too, no longer give birth.

The repetition of “Telipinu went” was inspired by a grammatical feature in these lines in the original—

dtelipinuš=a pait marmarri andan ulišta

Telipinu went, and he hid himself in the moor

In Hittite, to say “At that point / whereupon,” a sentence pairs the verb “to go” with the main verb of the sentence, in what is called the phraseological construction. So we can either read this as two clauses, “Telipinu went, and hid himself in the moor,” or we can read it as a single sentence that builds off of the previous information given in the text—“He brought away grain, Prosperity (deified), growth, abundance, and satisfaction; to the field, to the meadow, to the moors. Whereupon Telipinu hid himself in the moor.” Given the ambiguity of the grammar, does the phrase “Telipinu went” actually mean that he went somewhere, as we know he did? Or does the text use the verb “pait,” meaning “went,” in order to show a causal relationship between taking the good things away and hiding in the moor? This multivalency reflects the two main problems in the text—that Telipinu is no longer here and that he took the good things with him. His father, the Stormgod, says when he realizes why all the gods are still hungry, “Telipinu, my son, is not here. He became angry, and he brought away everything good.” This duality, that Telipinu left and that he brought away the good things, is captured in this sentence’s grammatical ambiguity.

What was the challenge of this particular translation?

It was difficult to bring the text far enough into conventional poetry in English, to make it recognizable to a culture removed by distance, millennia, and language from the original Hittite audiences. I have made a number of poetic translations of the Disappearance of Telipinu. For “Telipinu went,” I chose a form that would be familiar to readers who may never have heard of the Hittites. My translation is repetitive, rhythmic, and rhyming, relying on literary strategies which are not the dominant in the original Hittite composition.

For the words that we don’t perfectly understand, like šalḫiyanti– and mannitti-, terms that refer to some kind of good thing in nature, I substituted butter and chocolate. There was definitely no chocolate in Bronze Age Anatolia. I translated Hittite concepts of growth, abundance, and good things into the necessities, comforts, and luxuries of life, some of which have been constant for three thousand years, like housing, water, agricultural production, and love, and others that have been left behind—like messages from the gods inscribed on sheep entrails—or found along the way, like chocolate.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult? (Are there hard and easy translations?)

The first four lines of the poem came to me easily, at seven thirty in the morning at a café where I sometimes meet my friend Crystal and we write in each other’s company. I sat on those first lines for over a year—it took that long for the rest to come.

Understanding the Hittite of the original paragraph was not as challenging as it sometimes is. This stretch of the tablet is unbroken, and the cuneiform signs are neat and well-preserved. The poetic syntax is slightly unusual. Hittite is usually verb-final, but in the second clause here, “ḫalkin dimmarnin šalḫiantin mannittin išpiyatarr=a pēdaš gimri wēllui marmaraš andan,” which translates to “He brought away grain, Prosperity (deified), growth, abundance, and satisfaction; to the field, to the meadow, to the moors,” the field, meadow, and moors are shifted to after the verb pēdaš, meaning “he brought away.” They sit almost outside the sentence, forming an unusual grammatical feature that highlights how Telipinu brought these good things to places external.

The paragraph has a handful of specialized terms that Hittitologists don’t totally understand, like šalḫiyanti– and mannitti-. These words show up as a pair in Hittite texts and mean something like growth and abundance, although their exact meanings, as the Hittites would have understood them, are unclear. The Chicago Hittite Dictionary, which is the most comprehensive dictionary for Hittite words beginning with L, M, N, P, and Š, with T in the works, offers “growth (?),” with a hesitant question mark for šalḫiyanti-, and, with more certainty but less specificity, “(a desirable condition in nature)” for mannitti-. Comprehensive dictionaries for dead languages are projects on an epic scale and are a philologist’s most indispensable tool. The scholars working on these entries in the dictionary examined every instance that these words appear in Hittite texts.

When did you know this translation was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

In early attempts, I tried adding to the translation, expanding it into an epic poem that covered the entire myth, but the poem collapsed under its own weight. I’m glad I stopped where I did, because this smaller story’s focus on climate crisis would have been diluted among the activities of the gods running to and fro.

I did have some lines I was sad to part with, though, including

The eagle went, and it searched for Telipinu

It searched across the mountains, the valleys, and the deep blueIt searched over the slopes; the rocky, roadless wastelands

It searched until it flew exhausted back into the god’s hands.The Stormgod went, and he gathered up his tools.

He gathered up his hammer, his chisel, and his rules.

Do you regret any revisions?

No. In an early draft, I had “the science, the produce, and the cures” grouped together, like this—

He brought away the science, the produce, and the cures

He brought it to the meadow, to the marsh, to the moors.

I loved these lines, but I ended up breaking up and scattering these concepts across the poem. It took a lot of drafts to find a way to include science, produce, and cures in ways that made sense and worked! But breaking them up allowed me to bring in the last two lines, which I think improve the ending. In earlier drafts, I was going to end the poem here, with Telipinu bringing the good things to the meadow, marsh, and moors, but I like that I was able to use the current ending to say explicitly that Telipinu has left us all behind, which is the anxious subtext of the Hittite, who have themselves left us all behind.

Temple 1, in Ḫattuša (Boğazkale); the text was found not far away. Courtesy of the author.

Naomi Harris is a translator of Hittite poetry.

Leave a Reply