A male sparrow. Photograph by Rhododendrites, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

I. He Who Noteth

Everyone had fallen in love with the short (five feet, six inches), young (twenty-four years old), big-hearted leader of the Chicago Zouaves. Even Abraham Lincoln. The president and Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth were as “intimate”—these are Lincoln’s words in a letter to Ellsworth’s parents—“as the disparity of our ages, and my engrossing engagements, would permit.” Lincoln had given Ellsworth a job in his law office in Illinois and then invited the young man to accompany him on his famous inaugural train journey from Springfield, Illinois, to the East Coast. In his hopeful idealism, Ellsworth seemed to exemplify Aristotle’s description of the virtues of young people: “They have exalted notions, because they have not yet been humbled by life or learned its necessary limitations; moreover, their hopeful disposition makes them think themselves equal to great things—and that means having exalted notions.” In this account, the young are by nature uncynical, hopeful, magnanimous—in contrast to the pragmatic, fearful, and miserly old, who may maintain their grip on money but not much else; as Mary Chesnut puts it, “all other muscles are relaxed by age.”

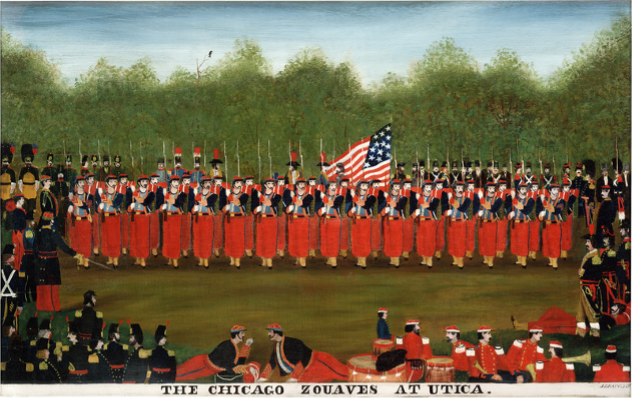

The son of a tailor, Ellsworth grew up in Mechanicville, New York. He had tried a few different lines of work before becoming preoccupied with infantry drills, poring over handbooks that taught the art of complex martial formations. Soon, he had taken over a drill team in Chicago, renaming it the United States Zouave Cadets (or the Chicago Zouaves) after the Zouaoua, a tribe that had been recruited into the French Army in the coastal Algerian mountains in the 1830s. The French developed these “exotic” uniforms, which soon became famous, to romanticize the colonists’ incorporation of local tribes into a European nation. The uniforms were the opposite of camouflage: ballooning red pantaloons, black jackets with gold, orange, or red trim, and fez-like hats (described in the Western Railroad Gazette of Chicago as “the jauntiest little scarlet head gear ever worn by a practical fighting man”). By the time of the Crimean War, 1853 to 1856, there were three Zouave regiments composed entirely of Frenchmen. Ellsworth may have heard about the Zouaves from his French fencing instructor, Charles A. DeVilliers, who claimed to have served in the Crimea in such a Zouave unit.

Drawing by J. Graff, 1859, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Ellsworth introduced drills that were as full of swagger as the uniforms, as well as an honorable code of conduct, called the Golden Resolutions, which forbade immoral behavior like drinking and gambling. Soon, Ellsworth’s Chicago Zouaves were touring the country to great acclaim. Thousands came out to watch their elaborate routines and to cheer on what was harder to name: the celebratory image of men at war. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the United States standing professional army was a mere sixteen thousand; the Union would soon have to rely on citizen militias, despite often their lack of actual combat training. Here is how the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported Ellsworth’s display of “martial acrobats” or “gymnastic soldiers” on July 14, 1860:

They fire a volley, and in an instant each man turns a back somersault, re-loading his musket as he turns, and comes on his feet ready to fire again; when charging a column of infantry, the Zouaves jump up twenty feet in the air and come down on the enemy’s heads with terrific force, driving them completely under ground. The killed are thus buried at the same time out of the way, which saves trouble. … When observations of an enemy’s country are needed, a Zouave is put in a sky-rocket and sent up to a sufficient altitude; being supplied with the necessary apparatus, he takes a photograph of the landscape, and by the time he reaches terra firma, he has a complete set of maps prepared.

In such descriptions, reality and fantasy blend. It is not even clear whether the reporter understands Ellsworth’s Chicago Zouaves as a real troop of soldiers—or more like the nineteenth-century equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters, who, for all their skill, are not exactly a team of basketball players.

After a crowd of twenty thousand came to see the Zouaves perform in Fort Greene on July 18, 1860, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle gently ventured a note of caution: “To one happily unfamiliar with grim-visaged war and all that pertains to it, some of the movements of the Zouaves are quite incomprehensible. For instance, when about to fall on their faces to protect themselves from imaginary foes, they turn an awkward kind of half somersault, which is not very graceful, and we will venture to say that if there were any danger of a random shot the Zouaves, like sensible fellows, would get down on the grass without any attempt at this acrobatic feat. When firing while lying on their face, not one musket was in a range that would hit anything above an enemy’s ankle.” The final line of this newspaper paragraph is an ironic coup de grâce: “Doubtless this looks different to military men.”

Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1860, p. 480. Public domain.

Like toy soldiers, Ellsworth and his men had become the object of a shared dream. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle compared him to Charles Blondin, who not only crossed Niagara Falls on a tightrope but did so on various occasions blindfolded, on stilts, with his manager on his back, and after having paused halfway across to cook an omelet. Ellsworth’s theatrics may have had little to do with the soldier’s actual duties of killing people and getting killed, but, really, who cared about such differences? When the Zouaves performed at West Point in 1860, even General Winfield Scott, nicknamed “Old Fuss and Feathers” for his love of martial spectacle, came out to see them. Lincoln’s private secretary, John Hay, commented that he had never in his life seen such magnetism as Ellsworth’s of “winning, fettering, moving, and commanding the souls of thousands till they move as one.”

As the country was transitioning from the small farms of the Jeffersonian ideal to the factories of industrialization, perhaps for a brief moment it still seemed possible to retain both the panache of human singularity and the perfect unity of the machine. Indeed, when the men were throwing their rifles over their shoulders, spinning, making elaborate formations in perfect synchronicity, did they not look like the interchangeable parts of a great machine, like the parts of a sewing machine, percussion revolver, or train? When one gear hooked into another, one piece flew forward to do its job and then, like the best servant in the world, leaped back into place without any shadow of resentment whatsoever—well, what couldn’t such a machine accomplish? By the end of the century, the Remington Company would be manufacturing not only guns and sewing machines but also typewriters, a machine is so clever that it looked like it could write a book by itself. William O. Stoddard, another secretary of Lincoln’s, recalled watching Ellsworth perform his drills: “How like a piece of human mechanism are all his clock-work movements!”

The Zouave fad spread: By the beginning of the Civil War in April 1861, there were about one hundred Zouave units in the country, mostly not intended for entertainment. Thirty thousand soldiers would go into battle wearing the dazzling Zouave uniforms. Ellsworth, who had received no combat training, was soon given actual martial assignments. After the presidential inauguration in March 1861, he was tasked with building a regiment from New York City firefighters, the Fire Zouaves. Everyone talked about their feats and pranks: how, stationed now in Washington, D.C., the men helped put out a fire at the Willard Hotel on Fourteenth Street by making of themselves a human ladder and how they climbed onto the dome of the Capitol, which was under construction, dangling their legs from two hundred feet up in the air. Or, did you hear how, after accidentally breaking a south window in the White House, Ellsworth and Lincoln’s secretary Stoddard amused everyone by pretending there had been an assassination attempt on the president?

Even the president probably found that one funny.

***

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, ca. 1861. Photograph by Charles DeForest Fredricks, albumen silver print, 9 × 5.7 cm. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. F. B. Wilde. Public domain.

Five weeks after Fort Sumter, the official starting point of the war, Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves received the command to sail down the Potomac River to Alexandria, Virginia, in the middle of the night. Before setting out, Ellsworth wrote the following letter to his parents in Mechanicville:

Head-Quarters, First Zouaves, Camp Lincoln, Washington DC, May 23, 1861

My dear Father and Mother. The Regiment is ordered to move across the river tonight. We have no means of knowing what reception we are to meet with. I am inclined to the opinion that our entrance to the City of Alexandria will be hotly contested, as I am just informed that a large force have arrived there today. Should this happen, my dear parents, it may be my lot to be injured in some manner. Whatever may happen, cherish the consolation that I was engaged in the performance of a sacred duty; and tonight, thinking over the probabilities of tomorrow, and the occurrences of the past, I am perfectly content to accept whatever my fortune may be, confident that He who noteth even the fall of a sparrow, will have some purpose even in the fate of one like me.

My darling and ever loved parents, good bye. God bless, protect, and care for you.

In his multivolume biography of Lincoln, the poet Carl Sandburg relates how Ellsworth—the son of a tailor, remember—hesitated about what suit to wear and chose a new uniform for his first engagement: gray with (a later biographer adds) a gold circlet on the chest that bore the Latin inscription NON SOLUM NOBIS SED PRO PATRIA, which means “Not for ourselves alone but for country.” Sandburg narrates vividly how Ellsworth then sailed out on the Potomac under “a clear gold moon [that] glistened on the bayonets.” Who would not have been charmed by this image? When the Zouaves landed in Virginia, “crowds of spectators lined a riverbank expecting the first battle of the war.” Ellsworth went to the local telegraph office possibly to stop Southern communications and thereby deter a Confederate attack on the capital. On King Street—later the site of a Holiday Inn—he passed the Marshall House, a three-story brick hotel. Flying from its flagpole was the rebel flag—a sight that had aggravated Lincoln, looking at it through a telescope from his study in the White House just across the river. Ellsworth promptly entered the hotel, ran up the stairs to the roof and, good Zouave that he was, cut down the rebel flag.

As he was descending the stairs, the hotel owner James W. Jackson suddenly stepped out of the shadows and—BANG!—fired a double-barreled shotgun directly at Ellsworth’s chest. The bullet tore through his uniform, reportedly driving into his chest the circlet with the Latin inscription about duty to country. And Ellsworth fell.

Dead? Of course, he was dead.

That is how—in all its dumb and abrupt brutality and lack of narrative sense—Ellsworth’s life story ended, cut short before it had fully begun. He was twenty-four. All the wondrous magnanimity of his youthful self, his good looks, his puckish humor were felled in the first instant of the war—in what was not even exactly a battle. His Zouave companion Francis E. Brownell immediately killed Ellsworth’s killer, first shooting him and then stabbing him with a bayonet.

Later that same day, Ellsworth’s body was transported back to Washington, D.C. A troop of Zouaves served as guards of honor around his casket. No one could believe that this charming young man was dead. He was the first Union officer to die in the war. Describing himself to a reporter from the New York Herald as “unmanned” with grief, Lincoln at first couldn’t talk—and then burst into tears. John Hay recalled that when brought to see the body, the president cried out, “My boy! My boy!”

Civil War envelope showing a portrait of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth with the quotation “He who noteth even the fall of a sparrow will have some purpose even in the fate of one like me.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress, part of the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Public domain.

Ellsworth’s death aroused strong patriotic feelings in the North. Enlistments increased. A Union pastor remarked, “We needed just such a sacrifice as this.” It wasn’t long before commemorative souvenirs were being sold that celebrated Ellsworth’s heroism. Among the surviving ephemera are sheet music (“Ellsworth Requiem”), a white ironstone pitcher that depicts the moment of Ellsworth’s death and his killer’s assassination in relief, both their arms flung into the air, and multiple memorial envelopes like the one shown above, which is preserved in the Liljenquist Collection of the Library of Congress.

Printed in two colors, the envelope depicts Ellsworth wearing a red Union hat set at a rakish angle and a blue regulation jacket, dark longish hair curls around his temples and jawline; his gaze is level. Note as well the beautiful penmanship of whoever mailed this letter, how the lines suddenly taper into streamers that seem to wave about in the air. (One biographer describes Ellsworth’s own penmanship as “dress-parade handwriting.”) The date stamp lands on the gorgeous first letter of the recipient’s first name, Louisa: a true meeting in miniature of eras and ways, of the powers of automatization and the arts of the human hand.

The envelope includes a line from Ellsworth’s final letter to his parents, which was found in his pocket after his death. The quotation is close to what Shakespeare’s Hamlet says before his death—“There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow”—which in turn is a version of Matthew 10:29, where sparrows also represent the smallest and least significant forms of life which God’s plan nonetheless comprises: “Not one of them,” Jesus reassures his disciples, “will fall to the ground apart from your Father.” The quotation registers a kind of hope that we, believers or not, might have for someone like Ellsworth: that his fall, too, can be countenanced, can be meaningful—if not in the eyes of God then at least in our everyday human eyes. Regardless, a sparrow is a good choice for this sentiment because it has always been a common bird.

II. A Dirty Shovel

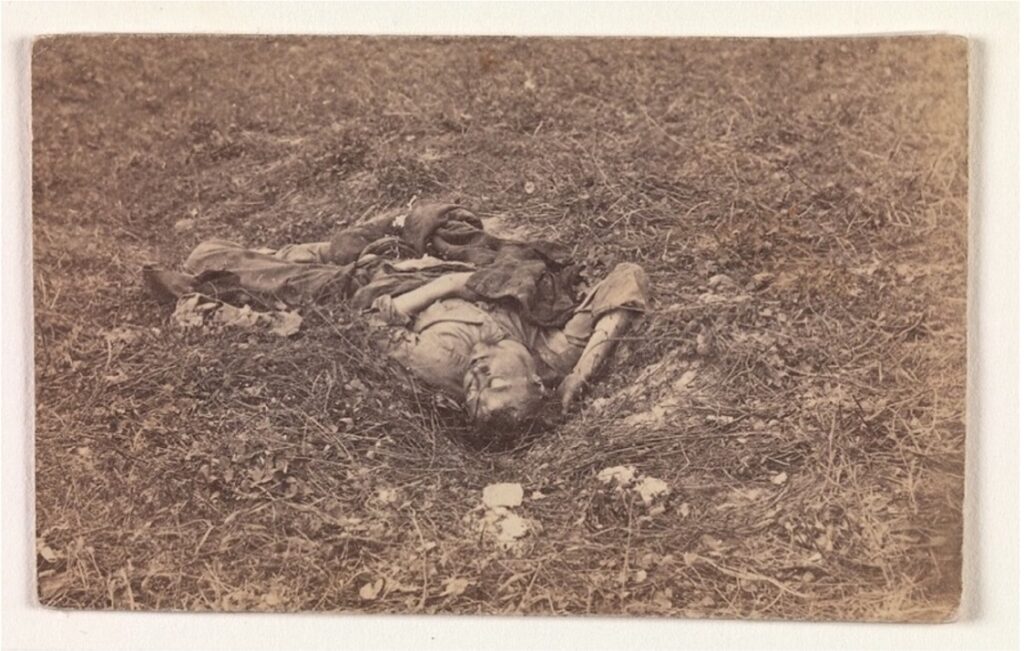

Alexander Gardner, Confederate Soldier [on the Battlefield at Antietam], September 1862, albumen silver print from glass negative, 6.1 x 9.8 cm. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Florance Waterbury Bequest, 1970. Public domain.

The reality of war turned out to be very different than the fantasy of it. After the battle of Antietam, which took place on September 17, 1862, the Scottish-born photographer Alexander Gardner went out into the field with his plate camera and took a series of photographs of the dead. Antietam was (and remains today) the single bloodiest day in American military history. After the battle was over, no one could believe how many people—twenty-three thousand—could be killed or wounded in a matter of hours when line after line of rifled muskets were blasting directly at their heads.

Gardner used plate glass negatives, sheets of glass coated with a solution called collodion (nitrocellulose in ether and alcohol), dipped into a bath of silver nitrate. He set up his camera in the field, mounted on a tripod, and peered at his chosen scenes from beneath a black curtain. The resulting pictures show people who would otherwise have left no record: here, for example, is a photograph of a dead Confederate soldier with his hand placed so delicately behind his head that he looks almost coquettish as he gives himself up to death. It appears as if he has dragged himself into a ditch to die, letting the land fold over him, sinking into it as Ophelia once sank into the muddy brook, “like a creature native and endued unto that element.” It is now known that Gardner’s team sometimes arranged the bodies or added a gun to make the images more visually affective. Most famously, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, which was taken on the battlefield of Gettysburg by Gardner’s assistant Timothy O’Sullivan, shows a barricade of rocks with a corpse that also appears in other photographs taken in a different location.

Indeed, it is not always easy to relate to the dead as fellow human beings. In one Gardner photograph, dead bodies with chests thrust into the air lie in a field of dried, trampled grasses beneath a rough-hewn fence. Another depicts a field with a wagon and, in the distance, a line of broken trees marking the slope of the land. At first, you don’t even notice the bodies, which, scattered this way and that, blend in among fallen fence posts. The title evokes the event of the battle, View on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862, while the image evokes the continuity of the landscape. And these two aims present a curious tension: the first asserts the memorability of what occurred there and the second its eventual oblivion and dissolution back into the waving grasses and gentle slopes of the land. One says that this event changes the course of things; the other that everything will go on exactly as if nothing happened here at all. One makes a claim for history; the other for nature. And both these claims produce a kind of comfort and a kind of terror. In looking at such photographs, I find that my eye again and again skips over the bodies of the fallen. I do not take in the obvious fact that every single one of them, when alive perhaps only a few hours before, must have contained a spirit as individual as that of Elmer Ellsworth’s.

In some Civil War pictures, I see living men who seem to anticipate that they will soon be dead. Consider, for example, this detail from an anonymous photo of the Fourth United States Colored Infantry Regiment:

Company E, Fourth United States Colored Infantry, ca. 1864. Photograph by William Morris Smith, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

In their uncanny power, the men’s faces resemble those of the Fayum portraits from the Roman Imperial era of the first century B.C.E. or C.E. onward, which were placed on mummies. The faces of the soldiers of the Fourth Infantry almost look like death portraits, for the men surely surmised that many of them would lose their lives. They, too, are posing for eternity. They were of the generation that, after the January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, chose, in the words of Barbara J. Fields, “to pay the price in blood, … to pay the price in blasted hopes and a lost future.” Sacrificing themselves for the sake of a future freedom that was unlikely to include them, they submitted themselves to the unyielding demands of their historical moment.

In Gardner’s Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862, a work crew stands beneath some blasted trees alongside the bodies of young people whom they must soon bury. These men also seem to exist on the very margin between life and death—but in a different sense, one that has more to do with fatigue and bodily exhaustion. Here the soldiers appear utterly wiped out, as though ready to lie down beside the dead on the ground. Notice how the soldiers do not even pose for the camera; rather, they submit to its gaze. “Take what you want,” these young people seem to say, “I would trade any idea of myself I’ve ever had for a hot meal and a bath.”

Alexander Gardner, Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862, 1862. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Florance Waterbury Bequest, 1970. Public domain.

One young man in this photograph I find especially arresting: the soldier on the far right, who is leaning on a kind of haystack of rifles. Is he looking back at me?

I made an appointment to examine a print at the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I did not confess that I was not actually a Civil War historian but a literary scholar who studies Shakespeare. To justify my interest, I could have pointed out how prevalent Shakespeare was in the nineteenth century: Abraham Lincoln was an avid reader of his plays and once expressed in an 1863 letter to the Shakespearean actor James H. Hackett his admiration for King Claudius’s soliloquy of guilt, “O my offense is rank, it smells to heaven,” from Hamlet, act 3, scene 3. (This speech may have resonated with the president’s own sense of responsibility for the deaths of so many young people.) I could have said that, at the end of the nineteenth century, an estimated five hundred Shakespeare clubs were scattered across the country. The abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass performed the part of Shylock in an 1877 reading of The Merchant of Venice at the Uniontown Shakespeare Club, in what is now Anacostia in Southeast Washington, D.C., and the Union general Ulysses S. Grant had been cast in the part of Desdemona in an Army production of Othello in Corpus Christi, Texas, before the Mexican-American War in the 1840s.

But no one asked me to justify my interest, at least not in any elaborate way. I simply filled out a brief form, and a couple of months later, a slender young man named Bobby was meeting me at the museum entrance. We chatted for a few minutes about I don’t remember what—this was October 2024, so probably something anxious and vague about the upcoming election—and then he brought me to a room with a long wooden table. I sat across from another young museum employee, who was cataloguing daguerreotypes. On a small stand in front of me leaned an original print of the Gardner photograph.

It was so small! Less than 3 x 4 inches, about the size of the palm of my hand. The concentration of detail was intense; I found that, if I leaned in closely, I could see the face of each soldier, even though each was hardly bigger than a speck of dirt.

With my eyes as close as possible to the surface of the photograph, I scanned the picture from left to right, as if reading it. Here was the line of dead, bloated bodies. Their clothing was disheveled probably because, just after realizing they had just been shot, soldiers reportedly clawed at their uniforms to see whether their wounds were mortal. Here were the trees, which themselves seem maimed. Here were the soldiers’ weapons, shovels, and pickaxes. The technology of guns may have changed but not, it seems, gravediggers’ tools. (“A pickax, and a spade, a spade,” sing the gravediggers in Hamlet.) Here were the grass and the dirt. Or perhaps these marks were the scratches that this grass and dirt had made directly in the plate. (The collodion process had to be completed within fifteen minutes, so Gardner developed his negatives on site in a makeshift darkroom in the field.)

I allow myself now to look at what I came here to see: the eyes of the final young gravedigger, the one whose left hand is partly covering his face. So tiny I can just barely see them, his eyes peer out from the print. How watchful is his gaze. The illusion is great that this young soldier in 1862 is looking back at me, as though taking the measure of my existence.

Detail from Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862.

***

By the end of the war, about seven hundred thousand Americans had died. They died of bullets, bayonet wounds, infections, disease. Some bodies were identified; around 40 percent were not.

Death on this scale seems to ask a question of us, although it is hard to say exactly what that question is. In her 2008 book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, Drew Gilpin Faust explores the problem of what death meant in this period. Relatives were often eager to know whether a son’s or brother’s or husband’s death had been a “good” one; that is, peaceful, dutiful, resigned to God’s will. Those who happened to be nearby when the soldier was dying often took on the task of informing families by letter about his last words. The humility of both the witness and the dying soldier in these letters is touching. Faust notes that Walt Whitman may have been an innovator of poetic form but that, as a nurse, he wrote hundreds of letters that told families as simply, consolingly, and uninventively as possible what had occurred in their beloved’s last moments. The dying soldiers themselves were just as eager to follow form. For example, when a doctor asked one soldier what to write to his family, the dying man responded, “I do not know what to say. You ought to know what I want to say. Well, tell them only just such a message as you would like to send if you were dying.” The soldier assumed that other people, surely the experts (like the doctor), must understand death better than he did. This soldier’s humble last wish reminds me of the sentry’s request in Hamlet that Horatio should be the one to talk to the ghost because, having been to college and having studied Latin, surely he knows what to say: “Thou art a scholar; speak to it, Horatio.”

We return to the dead not just to bury them but to make meaning of their deaths, even one hundred and fifty years later. Such historical remembering is also a kind of accounting for the dead, a tending to their known and unknown graves.

Rachel Eisendrath is the author of Gallery of Clouds, published by New York Review Books. She teaches in the English department of Barnard College.

Leave a Reply