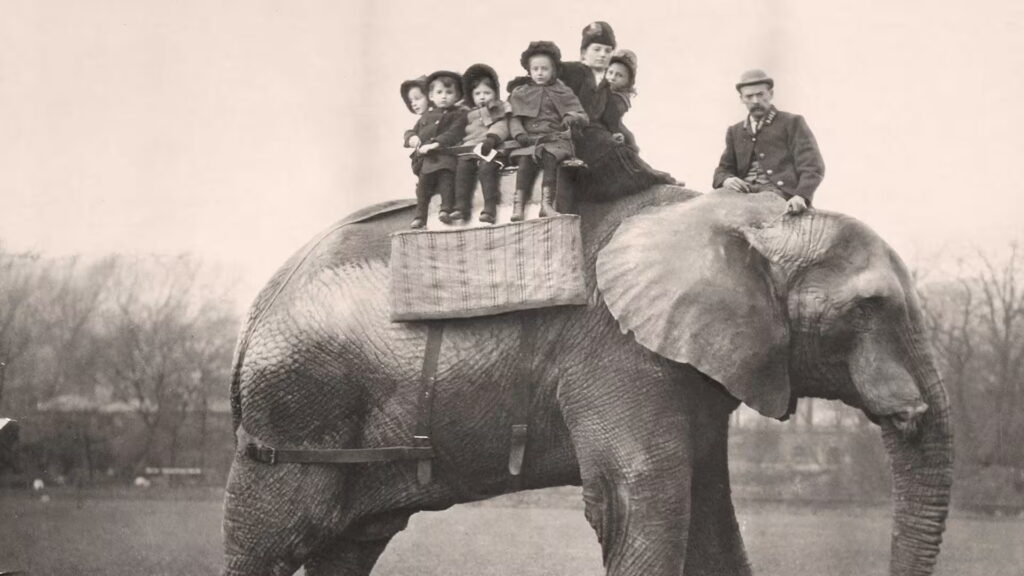

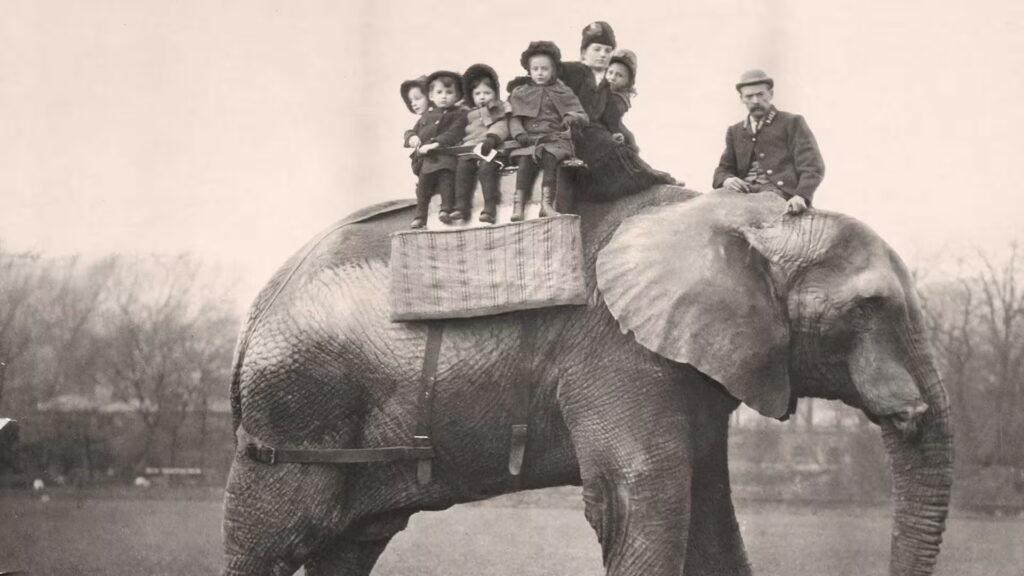

Jumbo the elephant. Unknown photographer. Courtesy of the Zoological Society of London.

We begin the essay with an uncited photograph from history. Roland Barthes speaks of photographs of children from history, their innocence and morbidity. To look at an old photograph of children is to look at children who are long dead. But the same is true for archival photographs of zoo animals. What do you see when you look at this photograph? A grouping of children in Victorian dress on top of a very large elephant, with a man keeping the whole contraption at a standstill. From what can possibly be read of the expressions of children from a grainy photograph, they look expectant, excited—the child zoo feeling. The elephant’s expression is far more inscrutable. Exhausted, possibly. Or just present. So present that photographs of this famous elephant from history always emphasize how much its extremely mammoth body fills the entire frame, or has been herded into a small enclosure (in fact, anything large began to be called jumbo because of the dissemination of his absurdly large likeness in advertisements). Why does John Berger begin with a photograph of Jumbo the Elephant giving rides to children at the London Zoo? Perhaps to situate the Eurocentric nineteenth-century zoo attitude, a narrative of colonialism and alienation from labor (absent while present), a story of tragedy and absurdity, the only possible tonal registers for the history of capitalism. Below is a much clearer photograph than Berger opens with, and the expressions on the faces of the one female chaperone and the children, and the familiar male zookeeper, are far more squinted and uncertain, but it’s unclear whether that’s due to the extremely large animal they are astride or to the even-less-familiar performative moment of photography.

Let me tell you a bit more than John Berger does, a story of Jumbo the Elephant, the most famous elephant in history. This is cobbled together from various reports, including David Attenborough’s 2017 documentary. The details often conflict. A male African bush elephant, his mother was killed by ivory poachers and big game hunters around the year 1860, somewhere near the Sudan–Eritrea border. Her tusks were hacked off the carcass to sell. The baby calf was captured and imported first to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, then transferred to the London Zoo, exchanged for one rhino, one kangaroo, one possum, a jackal, a pair of eagles, and two dingoes. The young elephant had to be nursed back to health upon arrival by his keeper Matthew Scott, pictured, who would sleep in his cage. He had a rotten tail and hoofs, his hide was covered in sores, as Scott writes in his autobiography, “I thought I never saw a creature so woebegone.” He was put to work giving children rides on his saddled back around Regent’s Park, a favorite of Queen Victoria’s children. Children would pay a fee to feed him currant buns. Jumbo lived for about twenty-five years, spending his life in captivity, first the zoo, later transferred to the circus, due to his fits of grief and rage becoming even more unmanageable as he reached mating age. (Grief and rage over his mother’s death? His relentless labor ferrying children? The claustrophobia of his small enclosures?). Scott would also prod and thrash the elephant, to try to tame his aggression, which he deemed adolescent. Jumbo broke his tusks by ramming against the walls of his cage at night, and when they regrew, he would grind them against the stone enclosure, in despair. There were night terrors, calmed only by a bottle of whiskey shared with his human companion and keeper. This repetitive self-mutilating behavior is referred to as stereotypic behavior, repetitive gestures exhibited by humans and other animals in distress, including in the caged conditions of zoo animals, such as also pacing around and around in a circle, which for elephants can accompany a quasidance that the filmmaker Chris Marker names “Slon Tango” in a four-minute film, part of his Bestiaire series, a long-sustained shot of an elephant in the Ljubljana Zoo ambulating around its enclosure, making seemingly syncopated steps to Stravinsky’s “Tango.” But Chris Marker’s eye here, as usual with his animals, is gentle and compassionate, there is a pathos to the slowness of the lumbering backstep of the Lithuanian soloist. For Tom McCarthy, in his dense, acrobatic Artforum blurb, the most important Marker motif is memory—perhaps, he theorizes, the elephant is actually remembering a historical past of a courtship ritual, or perhaps just a dance he’s choreographed for the duration of captivity, and he references, as so many inevitably do, the mythical newspaper article that apparently inspired Nabokov to write Lolita—the ape in the Jardin des Plantes who picks up a piece of charcoal to execute a sketch of the bars of his cage. Still to this day, zoos sell drawings or paintings made by their animals, who, the gimmick suggests, are really artists, although the labor of their constant work is, as with so many artists, made invisible by their gallerists/keepers. For the elephants picking up a brush, painting eases their anxiety, which is a feature of captivity, but one that can be remedied with a form of occupational therapy, or so the zoo’s own literature suggests. At the Cincinnati Zoo, the “brush in trunk” package comes with a custom canvas, with two photographs of your elephant (your elephant) creating the art, for the price of only two hundred dollars, plus thirty dollars for shipping across the United States. There is a list, at other zoos, of animals who paint—apes, inheritors of the late chimpanzee artist Congo, whose colorful expressionist paintings are collected by the filmmaker John Waters, but also a variety of other animals including giraffes, sea lions, rhinos, and hippos, as well as lizards, snakes, and penguins.

What am I performing here? Something like a bestiary. A collection—that was the Victorian zoo language. When in 1882 P. T. Barnum purchased Jumbo for his collection, one hundred thousand children wrote to Queen Victoria to protest. But not only was Jumbo’s aggression seen as a possible danger, there was also concern that a mature elephant’s erections would be too much for a Victorian crowd. He was shipped off to America with Matthew Scott, in a crate that barely fit his six-ton body, plied with alcohol to calm him. He was photographed arriving with his trunk waving out of his crate, promenaded to Madison Square Garden to be exhibited. I am still of an age to remember the Ringling Brothers Circus, before the elephants were retired—in fact I am roughly the age John Berger was when he wrote his treatise on looking at animals at zoos, also finding myself at middle age with young children, taking them to zoos, despite my ambivalence. My aunt would take us, as well as to the popcorn movies, and we would eat pink cotton candy. I remember weeping while watching Dumbo in the theater with my aunt, a story of a young elephant, with his ears for flying, who is taken from his mother and forced to be a circus performer, inspired by Jumbo. At the Ringling Brothers Circus, I can remember seeing in the ring, the circle of elephants. Jumbo was only in the circus for three years, making P. T. Barnum millions. Famously he died being struck by a train in Ontario, Canada, while being shuttled by Scott to his boxcar, although there is still a mystery as to the circumstances. Was it an instant death, due to his tusk becoming lodged in his brain, or is there truth to the story Barnum gave the press, that he was trying to save a smaller elephant, Tom Thumb, from the oncoming train? Was he always dying of tuberculosis and Barnum paid off Scott so that he didn’t hurry his charge along the tracks? Jumbo’s hide was mounted and exhibited for a four-year tour, then sent to Tufts University, where Barnum was a trustee, where it burned in a fire, and his eleven-foot-tall skeleton was donated to the American Museum of Natural History. “If I can’t have Jumbo living, I’ll have Jumbo dead, and Jumbo dead is worth a small herd of ordinary elephants,” Barnum said to the New York Times. According to Jumbo’s postmortem report, his stomach was revealed to contain “a hat-full of English pennies, gold and silver coins, stones, a bunch of keys, lead seals from railway trucks, trinkets of metal and glass, screws, rivets, pieces of wire, and a police whistle,” the souvenirs of a life in captivity, and from snatching coins from the children. An important early memory for the artist Joseph Cornell was seeing Harry Houdini at the Hippodrome with his parents. I don’t know this for sure, but I like to think it was in 1918, when he would have been fifteen years old, and Houdini disappeared Jennie the elephant into a huge cabinet (the illusion is difficult to explain, but basically Jennie took her sugar, sauntered into the front of the cabinet, and then twelve men pivoted the cabinet so that when it opened it appeared empty, because of a black interior curtain. This section of the bestiary is beginning to feel like a huge cabinet to fit the elephant. Turn it around and around and eventually all the elephants will disappear.

During the Second World War, a majority of the animal inhabitants of Japan’s Ueno Zoo were killed in secret by their keepers, either by starvation, strangulation, or blows or spears, or poison, specifically strychnine, which produces a slow, painful death, first muscular convulsions then ultimately death by asphyxia or exhaustion. But three remaining Indian elephants—John, Tonky, and Wanri—known by children throughout the empire—were starved to death, when the poison did not work, which took up to four weeks, despite repeated efforts by the elephants to perform tricks to get treats. A children’s picture book, Faithful Elephants, which literally translates to “poor elephants,” written by Yukio Tsuchiya and published in Japan in 1951, depicts the army as requesting that the Japanese zoo poison their large animals, because they were worried that they would escape and harm the public in the case of a bomb detonating nearby. Tsuchiya has said she wrote the book so that children would know the grief caused by war. But what really happened in the summer of 1943 is less clear—there are reports that the governor of Tokyo ordered the slaughter of the large animals at the zoo for propaganda reasons, to shock the residents of Tokyo into supporting the realities of war. Besides the elephants, twenty-four residents of the zoo were executed, including bears, lions, a leopard (poisoned), polar bears who couldn’t be starved and so were strangled by wire. A memorial service was held for the animals by government officials, attended by the governor himself, as well as hundreds of school children, who were the designated audience. The animals were mourned as martyrs for the country. The animals went to their death so the people would know the inevitability of air attacks. It was a death by honor. In the children’s letters originating from all over Japan, they were upset and furious with America and Britain for causing these beloved animals to have to be killed. The proper nationalist feelings were stirred, as so often is the case with a nation’s feelings toward the animals they feel they own. See another zoo celebrity, Knut the polar bear in Berlin, satirized so memorably in Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear, his rejection by and orphaning from his also captive mother at birth representing his generational alienation from her maternal past as circus performer and from his grandmother, a Russian émigré writing of her experiences in the minor language, just like Kafka’s lecturing animals. Knut the polar bear became the cause célèbre symbol of our climate crisis, the unnatural environment of the zoo a reminder of global warming, superimposed while at the Berlin Zoo by Annie Leibowitz on the cover of Vanity Fair with Leonardo DiCaprio, who was on a glacier lagoon in Iceland. The real Knut died at the age of four having suffered a seizure and drowned with a splash into his pool while people watched. The theater of heartbreak and mourning that unleashed—with fans leaving the stuffed animal versions of him near his cage. He was taxidermied and put on display at the natural history museum, enshrined in a bronze statue, the typical process of mourning for revered zoo animals that also helps to ease the real, hidden, loss for the city, that of touristry and ticket sales. It’s not easy to make a successful animal statue, especially of a polar bear. In nineteenth-century Paris one trained to be an animalier, as Rodin did with Antoine Barye. There is the marble sculpture by François Pompon, assistant to Rodin and Camille Claudel at the Musée d’Orsay. How does one get the fur right, the tones of the white fur the nature writer Barry Lopez began to refuse to photograph and that Tawada imbues with such painterly surrealism. Pompon also eschewed realism and went for the intuitive, essential nature of the polar bear. Colette admired the “thick, mute” paws. After my first zoo report, about the melancholy and strangeness of monkey cages, was published, someone wrote me: “I wonder if that melancholic quality is part of what appeals to children about zoos—they have so few opportunities for indulging their own melancholia, especially girls, so much pressure to have everything unicorns and rainbows.” This felt profound to me, especially since this writer is the author of a forthcoming biography of Anne Frank, the iconic melancholic young girl, meditating upon her adolescent feelings, set amidst her attic captivity. I wonder if the zoo is a place where young children can feel these intense feelings of sadness and mortality, including the deep formal mourning for zoo animals that are extinct, or have died in the conditions of their captivity.

Chris Marker’s elegiac memory film, Sans Soleil, is like a menagerie, occupied by so many animals and their funerals, from a shrine to missing cats to the death of the panda at the Ueno Zoo, most likely the death of Lan Lan in 1979, along with her “groom,” Kang Kang, a special gift from China to the people of Japan, who might have delivered the first giant panda born in captivity had she lived one more month. The female narrator, reflecting on a letter that the Marker alter ego Sandor Krasna wrote her, meditates upon the funerals for animals in Japan, with the same chrysanthemums as are customary for the funerals for humans, a day of mourning for all animals that died that year intensified by the panda’s death, which was experienced with more grief than when the prime minister died at approximately the same time. Perhaps this day of mourning for the dead panda, and the ritual of weeping, brings about a catharsis as Aristotle describes in his poetics on tragedy. “I’ve heard this sentence: ‘The partition that separates life from death does not appear so thick to us as it does to a Westerner.’ What I have read most often in the eyes of people about to die is surprise. What I read right now in the eyes of Japanese children is curiosity, as if they were trying—in order to understand the death of an animal—to stare through the partition.” The juxtaposition of daily life and the passage of time in Guinea-Bisseau and Tokyo in Sans Soleil, first the Japanese children laying flowers at the funerary scene at the Ueno Zoo, then a cinematic gunshot from a B-film, seemingly the poachers aiming toward the giraffe in Africa, who first runs around, staggers, then crumples to the ground, the almost ecstatic horror of the spurts of blood flying out. A quick shot of a chrysanthemum flower juxtaposed with the unmourned face of the dead giraffe, being picked at by vultures. Only banality, the ephemerality of time, interests the traveling documentarian Sandor Krasna. “On this trip I’ve tracked it with the relentlessness of a bounty hunter.” So is the giraffe then a metaphor, or some elegiac statement about different attitudes toward animals and mortality, or both? All animals in Chris Marker’s films are political, writes Tom McCarthy. There was an outcry at the Copenhagen zoo where Marius the baby giraffe was euthanized by a rifle, publicly dissected, then fed to lions. He was healthy but genetically unsuitable for captive breeding programs, apparently. The children didn’t cry, newspaper reports read. They were curious and asked questions. During the most recent pandemic, when zoos were closed to the public, there was an ambient paranoia about what might happen to the animals without paying customers, including from one German zoo who threatened that the animals might have to be fed to other animals if they couldn’t afford food. The last on the food chain would be their twelve-foot-tall polar bear. This somehow parallels the abovementioned fear about large animals running free during the European world wars. Germany shot many of their large animals in advance of air raids. Those not shot were killed in other ways, such as the elephants at the Berlin Zoo. The London Zoo killed all of their poisonous snakes at the beginning of the Second World War. The Antwerp Zoo killed some of their large animals during both world wars. The hoofed animals slaughtered because of the food shortage. Others froze to death. The Egyptian temple, housing the giraffes, collapsed. Sebald describes the Antwerp nocturama in the opening pages of Austerlitz, his lists of the nocturnal animals also like a bestiary, reminiscent of Borges’s imaginary creatures, which Sebald cites throughout his works, including Rings of Saturn. His only lasting memory of that zoo is of a raccoon washing a piece of apple over and over again. I wonder if Sebald knew of the tragic story of Rembrandt Bugatti, younger brother of the automobile manufacturer, who would spend days at the Jardin des Plantes, studying the animals he watched there as the subjects for his bronze sculptures, like his walking panther, the beauty of his carved muscles. This was around the same time Rilke was studying his panther at the same Paris zoo for hours, his exhausted vision from the passing bars, at the advice of Rodin, who was known to carry a small carved model of a panther in his pocket for inspiration. It is most likely that the poet and the animalier were together, in front of the panther cage, forming their own imagined bonds with the animal, if the dates line up correctly (1904 for the panther sculpture, between 1902 and 1903 for Rilke’s poem). Both found solace from their financial troubles and bouts of depression standing at that zoo, watching the animals. The sculptor volunteered as a paramedic at an Antwerp hospital during the First World War, and would spend his time off at the zoo there, in companionable silence with the animals. After his friends were slaughtered due to food shortages, he himself committed suicide.

***

In Sans Soleil the Marker alter ego tells us, through his distanced address, that he has spent his days in front of the TV, “that memory box.” For me over the past year it’s the laptop. Has it really been a year since I’ve been to the zoo? My zoo feelings have been memories, usually historical memories that are not mine, from what I’ve gleaned from reports read online and in books. The zoo narrative this year in New York City was the Eurasian eagle-owl Flaco, who escaped his enclosure at the Central Park Zoo when someone cut his stainless-steel netting. He lasted nine months eating rats and pigeons while being spotted on Manhattan high rises and in the park. There was a debate about his survival in the wild, whether he should be captured again, a narrative of captivity only complicated when he died from injuries colliding into a building, and was found with high levels of rat poison in his system as well a severe affliction of pigeon herpes (please ignore the comments about this, that assume Flaco was doing something else with the pigeons, other than eating them, to get herpes). I only viewed the crowded memorial service at Central Park online, with crayoned drawings of the owl, signs proclaiming FLY FREE FLACO! even in death. I am reminded of the funerals for birds my children would hold in Prospect Park, during summer camp, although not aware the birds have most likely died in such number because of rat poison, feral cats, or perhaps the intense heat. Children are instructed into the lives of animals usually through the death of insects, although they are not as aware that those are disappearing as well. The history of the zoo is now also footnoted with its relationship to natural and manmade disaster. It was only this spring that I became aware that our local zoo had been closed since the flooding last September because of damage to the electrical grid. Twenty-five feet of water in the basement. None of the four hundred animals apparently were harmed and they got to stay in their habitats. Were those inside just in the dark, without electricity? The person cutting my hair, who has two children the same age as mine, informed me of the closure. How was I not aware? We had withdrawn into our private family unit, alienated from the natural world, locked into a pattern of work and school, just as John Berger predicted. As I write this it’s now Memorial Day weekend. The zoo is opening up again. Look, there are new baby baboons.

Leave a Reply