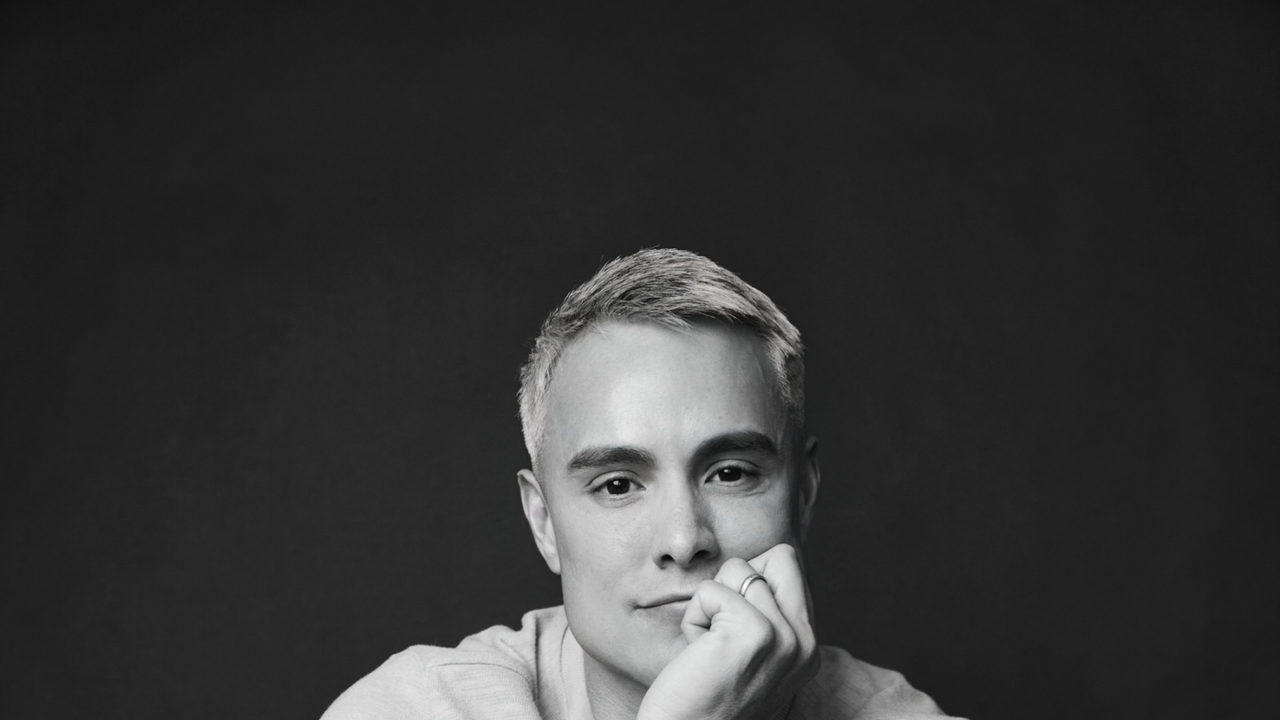

Today’s post is by author Lesley Krueger.

Late last fall, the forecast called for one last day of sun and warmish temperatures. It was time to take down the garden for winter. After plotting out my work, I started with the small garden in the front yard. First I cut down the yellowed lilies, daisies and hostas, the coral bells and violets, keeping my head down as I bagged them. Raked the fallen leaves and bagged them too, then took them into the garage out back to store until the city’s pick-up date.

As I left the garage, I glanced up. Just that moment the sun came out, lighting the golden crown of a tree across the lane. It was a silver maple far older than any of us, and it rose high above the rooftops. Its pale bark make it look like an enormous birch, the full crown of golden leaves glowing against a pale blue sky. A faint wind blew and the leaves rippled, reverberated, emanated autumn. I felt completely happy.

Then a cloud blew in and the color faded. I smiled and shook my head, picking up my rake and getting back to work.

Happiness. We tend to underrate it in writing, caught up in the technical questions of maintaining tone, pacing, momentum, action. A pause to enjoy life, like the one I took, seems extraneous. Better cut it. Kill your darling.

Yet hitting pause at a well-chosen point can add immeasurably to a piece of writing, fiction or non. And I remember a particular time when it was missing.

Beginner mistake. No blame.

A while ago, in a creative writing class I taught, a young man turned in a story he was very proud of, which meant he was remarkably defensive when other students gave notes. It was about a couple living in a trailer park. The man was a drunk who beat his wife. The poor woman was forced to take a job as a greeter in a Walmart, which she hated. She didn’t earn enough to fix the leak in the roof of the trailer, so the place smelled of black mold. Even the cat was scabby. Then things got worse.

Someone in my family worked as a Walmart greeter for a while. She’s a sociable, good-humoured, helpful person who liked the job. Her husband is a tradesman and they do all right, but their kids had left home and she was bored, and who couldn’t do with a little extra cash? So she worked there for a couple of years until she had to quit to help raise a grandkid; long story. She told me once how much she loved looking down the aisles at the long rows of neatly arranged products; the blocks of bright primary colours. She had a shy idea to communicate to a writer: “It’s like a circus is going to break out any minute.”

Let’s just say my student looked well-supported. Maybe he had no Walmart greeters in his family, or none that he’d met. In that case, he could easily have done some research. Walmart has done away with greeters, but at the time he could have walked into a store and greeted one, since it’s their job to talk. He could have chatted them up about the job, listening for details that would make his story jump. He might even have discovered something that made them happy.

Yet when other students questioned the implacable bleakness of his story, the young man pushed back. He was concerned with maintaining his tone. You needed to keep it consistent. Keep up the forward momentum. Above all, make your point efficiently.

One woman semi-quoted Leonard Cohen back at him. “There needs to be a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

“That’s such a f—g cliché,” he replied.

Take that, Leonard.

But of course the woman was right. An unrelenting tone puts readers off. It’s both wearing and unrealistic. Life always has moments of beauty. And frankly, it’s condescending to characters lower down the economic ladder to portray their lives as nothing more than drudgery. Or, if they’re higher up, to make them one-note villains or snobbish comic foils.

Say my student’s character is putting in her shift at Walmart, and has a lovely moment imagining the aisles letting loose their circus. When she gets home, her husband roughs her up. But as he raises his tattooed fist, she blanks out the violence, dancing down the aisles at work with a trained bear.

Afterward, she brushes her perfectly well-fed cat, who blinks at her adoringly. The husband collapses beside her, growing smaller with contrition, and soon demands she console him for having hit her. It happens again the next day, then again, then maybe it doesn’t or maybe it does. Whatever the writer’s choice, the story isn’t ploughing forward unremittingly, but has interludes and switchbacks and moments of joy.

Is it all about pacing?

I recently found myself marveling at Rachel Kushner’s technique while reading her latest novel, Creation Lake. It’s a brilliantly written, rather eerie story about an undercover operative. The woman has been hired by shadowy forces to infiltrate a commune of environmental activists in France, instructed to discredit them and undermine their opposition to a new dam. If she can get them to kill an inconvenient politician, that’s a bonus.

The operative is American, but we never learn her name or anything about her family. No memories, no grievances, just a few details about a failed U.S. intelligence job that forced her to switch to international ops. There’s an important story line involving the commune’s guru, but the book relies heavily on forward momentum. It’s an accomplished version of what my student had hoped to achieve.

Despite this, Kushner repeatedly allows her narrator interludes of happiness—scenes that serve purposes in her story other than slowing the pace.

One time the operative is driving through France.

I was on toll roads, pulling over to drink regional wines in highway travel centres, franchised and generic, with food steaming under orange heat lamps, each of these travel centres offering local products. Lavender oils, for instance, always made at monasteries, as if the monks worshipped lavender instead of God. Or dried truffles, mustards, and glass jars of jellied meats that look like cat food, and which French people call a ‘terrine’ and eat as if it were not cat food…

I enjoyed a white Bordeaux of Médoc provenance in pleine aire at a roadside fuel stop where a trucker farted loudly while paying for his diesel at the automatic pump, the loose valves of his truck, like his own loose valves, clattering away. The white Bordeaux was smooth as a silk garment in a virgin’s trousseau. I could have been a little buzzed by this point, five hours into my drive. This cold, dry white wine sent me dreaming about a world where all my clothes were white and I slept on white sheets and would never be traded for a dowry or violated by rough and unworthy men or forced to drink anything less than the finest white wines of the smallest and oldest and most esteemed appellations, and in a way I could say that I was living that life, right here at this gas station. At least in spirit I was.

What is Kushner doing here?

The scene occurs early in the novel. Notice what we learn about the operative. She drinks while driving, unconcerned about breaking the law or, hmm, say, killing someone. Maybe she’s got a problem with alcohol, although she stays sharp, noting details like the particularly orange light of a heat lamp. She has a loopy sense of humour—cat food terrine—and doesn’t seem to like men very much. A trucker at the gas pump farts, and she laughs to herself about his clattering valves. She also dreams of not being violated by rough and unworthy men, a hint that she has been.

By hitting pause during a pleasant interlude, Kushner illuminates her operative’s likes and priorities in a way she can’t in the middle of an action sequence. Note that she doesn’t do this through flashbacks. We don’t get, “I remember when…” or, “I admit I was the type of kid who…” Instead, we get to know the character by seeing the world as she sees it, learning what gives her pleasure, where her priorities lie, and what weak spots might trip her up later.

Some might say: this scene doesn’t advance the plot. Cut it.

Maybe not.

Are there other ways to deploy happiness?

In Creation Lake, the driving scene comes near the beginning of the book, and proves useful in introducing the main character. But narratives work best when characters enjoy themselves at other points in the story, even in fast-paced genre novels. The reader occasionally needs time to breathe; the protagonist a moment to think. Writers need to learn when to let this happen.

I was reviewing a new mystery recently and pulled A Certain Justice off my shelves, a P.D. James novel published in 1997 that features her detective, Adam Dalgleish. I’d remembered that James is very good at introducing her murder victims, setting them up in such compelling detail we’re driven to find out who killed them. Yet she doesn’t portray a victim so sympathetically that their death comes as a blow. If we like them too much, a detective novel becomes less an intellectual cat-and-mouse game and more of a classic tragedy.

What I’d forgotten before re-reading James’s book is that she’s equally good at knowing when to hit pause. I love mysteries, but sometimes the action feels so unremitting that I flip to the end, wanting to ease the tension and find out whodunnit. A Certain Justice kept me hooked by breaking up the headlong action with interludes of peace and joy.

Page 342:

It was another perfect summer day and Dalgliesh at last threw off the western tentacles of London with a sense of liberation. As soon as he saw the green fields on each side of the road he drove the Jaguar onto the verge and put down the hood. There was little wind but as he drove the wind tore at his hair and seemed to cleanse more than his lungs…

But suddenly he was struck by an imperative need to glimpse the sea. Crossing the main road, he drove on toward Lulworth Cove. At the breast of a hill he stopped the car and climbed over into a field of shorn turf where a few sheep ambled clumsily away at his coming… He had brought a picnic of French bread, cheese and paté. Unscrewing the Thermos of coffee, he hardly regretted the lack of the wine. Nothing was needed to enhance his mood of utter contentment. He felt along his veins a tingling happiness, almost frightening in its physicality, that soul-possessing joy that is so seldom felt once youth is past. After the meal he sat for ten minutes in absolute silence, then got up to go. He had had what he needed and was grateful. A drive of only a few miles toward Wareham brought him to his destination.

Useful beasts, cars. They often allow for interludes, detours, a change of mood and pace. On the previous page, a member of Dalgliesh’s team reveals that he suspects a particular woman of murder. Dalgleish is about to interview a different suspect in Wareham. If James had rammed these scenes together, things would have felt a bit: and then, and then, and then.

Instead:

- James allows us to catch our breath, along with Dalgliesh.

- Like Kushner, she adds character to her protagonist, at least a little. Since this is the tenth Dalgleish mystery, James doesn’t need to do much of that. But here she wreaths a sense of melancholy around her detective, and reminds us that he’s no longer young.

- There’s also this: James ends the interlude by sending Dalgliesh off to Wareham. Yet since she’s slowed the pace, the next section can begin more discursively as he interviews new suspects. When they begin to behave oddly, the action can speed up again. Speed up. Speed up some more. Then James hits the brakes with another happy interlude before flooring it and sending Dalgliesh hellbent toward the climax.

How do you know when to slow things down?

Some people have a natural, musical sense of the rhythm of writing. In the work of students, of friends to whom I’m giving notes, in novels I’m editing, I’ve found over the years that some people immediately nail pacing, just as others are naturally good at dialogue, description, characterization, plot, whatever. Few writers have a full toolbox when they start.

I had to learn pacing, myself. And here’s something I would find. It helped to print out a long section of whatever novel I was working on. I’d read it over slowly, clinically, looking for the point where I got bored with my own prose.

There are many reasons this fatigue can surface. Usually the work needs cutting. But sometimes I’d conclude that while everything that was happening needed to happen, the constant forward momentum wasn’t sustainable without breaks.

I learned not to start my rewrite at the point where I got bored. Instead, I’d move back to the beginning of the chapter and open with the sort of interlude of happiness that James allows her detective. I also found that happiness is what works. Notice how James says Dalgleish feels “utter contentment,” and “soul-piercing joy.” After ten minutes, she writes, he had what he needed, and so have we.

Looking back on my day of gardening, I see that I did what I do every year, cutting down the flowering plants, raking up leaves. The specifics will eventually run together. But I suspect I’ll always remember that sunlit tree: the silvery bark, the high blue sky, that nimbus of gold.

Also how it faded, and I smiled.

Lesley Krueger writes a Substack newsletter called Alive to the World. It centres on research and writing tips, and subscriptions are free. Her latest novel is Far Creek Road from ECW Press.

Leave a Reply