All photographs by Oliver Egger.

IJust as the sun begins to peek over the flat horizon of Coon Rapids, Iowa, 1,383 pigeons fill the sky. The birds pour out as a single winged mass from the rows of flung-open coops on the transport truck. They rise and circle higher into the morning air. Strong gusts from the south-southwest soon scatter them into hundreds of solitary black dots across the slabs of clouds.

They could fly anywhere. They could head north to go swimming in the cool rush of the Middle Raccoon River. Go southwest to inspect the quality of lampposts in Omaha. Or simply land on and rest in one of the maples below. But each pigeon, as if pulled by a magnet, turns due east. They flap their wings as fast as they can until they disappear over the horizon—all heading toward Chicago, all heading home.

Or so I heard. While the pigeons were being released on that morning of Friday, October 17, in a field in west-central Iowa, I was nearly four hundred miles away, sitting in a dinky Sheraton Hotel near O’Hare Airport for the board meeting of the annual convention of the American Racing Pigeon Union (ARPU). The ARPU is the largest pigeon-racing organization in America, with 6,650 members, but this summit on expanding vaccine accessibility for their birds, boosting youth participation, and updating pigeon tracking software was before an audience of no more than fifteen, which, as one hour became two, dropped to a die-hard five.

As a man in a USA trucker hat rose to ask the board about their pigeon lobbyist (yes, even they have one), the hundreds of airborne pigeons were locking on to the exact coordinates of the home lofts—scattered in backyards and garages within a fifty-mile radius of this hotel—where they had been raised. As they soared over cube-cut farmland, scanning for hawks with their orange eyes, they had no idea that fifty thousand dollars were at stake, that the humans that raised them were anxiously waiting for them to swoop in, or that they were competitors in the convention’s main event: the yearly ARPU combine. No, they were just trying to get home.

***

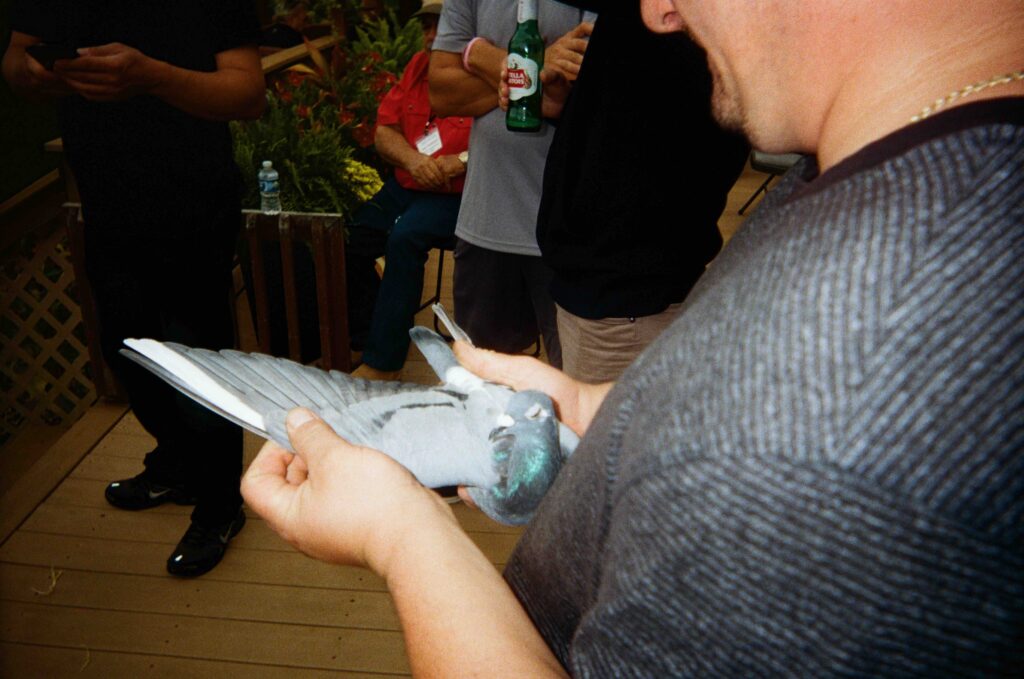

The race had really begun the night before, when this convention hall hosted a more raucous affair. It was packed full of nearly a hundred fanciers—the name for people who breed and race these aptly named homing pigeons—each holding a wooden crate loaded with several wide-eyed pigeons curled on sprinklings of hay. They were there for “shipping”: registering and loading their birds on the transport truck that by midnight would set off an all-night journey to Coon Rapids.

The room overloaded the senses: the earthy stench of animal mingled with the artificial tang of jumbo bags of Cool Ranch Doritos and freshly cracked Coca-Cola cans, into which Jack Daniel’s was poured from a passed-around handle. Conversations, overlapping in Polish, Spanish, and English, were punctuated by the frequent, piercing beeps of the racing bands fastened around the birds’ legs being scanned at a table up front.

I noticed that the fanciers, almost all male and wearing neon pigeon-adorned T-shirts freshly pulled out of a Custom Ink box, often stopped their conversations and looked me up and down when I walked past. I had no crate, no pigeons, and was probably thirty years younger than anyone else in the room. That could mean only one thing: undercover animal rights activist.

An older woman with dyed-red hair at a desk by the door called me over and asked, in a thick Polish accent, for my name. I told her. She scanned a piece of paper with the end of her pencil. “I don’t see your name on the list,” she said loudly. Heads, bird and human, turned. “Umm … I’m here to write about the convention …” I remembered I wasn’t in fact an undercover intruder. “Al knows I’m here.”

“Crazy Al?!” the woman asked.

“Yeah … ?”

She seemed to calm down. “Oh, okay.”

Al Christeleit, or Crazy Al, is a seventy-eight-year-old no-bullshit Coloradan with a white mustache, a glistening pinkie ring, and an oxygen tank with clear tubes attached to his nostrils, who currently serves as the president of the ARPU. I escaped from the red-haired lady and found him at the back bar surrounded by fellow fanciers and empty bottles of Miller Lite. “He’s got nothing to do with PETA!” he declared to the group. It had taken several weeks of serious convincing to prove to him that I wasn’t, and for him to let me attend the convention.

He then launched into a story of a PETA lawyer who had infiltrated the 2016 convention, calling the police on them and trying to get the hotel to shut down the event by claiming they were illegally gambling on the races. All had seemed lost until an old friend of Al’s rushed in and saved the day: proving the sport’s fidelity to the law, calming the anxious desk clerk, and telling that young upstart lawyer to “get the hell out of here.” (I heard Al tell this story at least five more times before the weekend was up.) He emphasized that there is no gambling at ARPU pigeon races and that the winning pot is split from the entry fees for each bird. “It’s just like the rodeo,” he said, slapping his large hands on the table.

The main complaint from animal rights activists isn’t gambling, but that many birds will never return home from the races. There is no definite research on what percentage of pigeons die or get lost during an average event. PETA estimates more than 60 percent, while the fanciers claim it’s more like 10 to 15. It’s impossible to verify from race results because most events count only the pigeons that return by nightfall, but many will roost in a tree overnight before returning home the next day, or even multiple days after the official count has ended.

And while the fanciers who were gathered around Al each in turn insisted to me that they never want anything to happen to their birds, they clearly took a certain pleasure describing the long list of perils the birds face on their journeys. “You don’t know the weather, the wind, the hawks, being hungry, or whatnot,” one long-time fancier told me. He added, with a note of reverence in his voice, “All those dangers that they face, and they manage to return to their home.”

***

That Friday at around noon, after the meeting at the convention center ended, there was a buzz of excitement as everyone rushed off to catch rides to friends’ houses. It was time for the main event: watching the birds come in. When I asked Dave Wilson, a board member from Ohio, what to expect, he laughed. “Nothing.”

I caught a ride over to Andy Waclaw’s house in Lemont, a suburb southwest of Chicago. (All the lofts are outside Chicago proper because, since 2005, the city has had a ban on keeping of pigeon lofts after complaints from residents and animal rights activists. Quite the sore subject at the convention, as you can imagine.) Andy, who immigrated from the small village of Czarna Góra, Poland, as a child, is a forty-four-year-old executive assistant for the Cook County treasurer. He is also one of the top fanciers in the country, known for raising arguably the most award-winning bird in U.S. pigeon-racing history—a green-and-purple-necked beauty named Miss America.

While the birds are the athletes in pigeon racing, the human contribution to the sport is twofold: breeding and handling. Pigeon breeders aim to produce birds with ideal characteristics for speed and navigation by selectively mating birds that have won previous races or come from winning pedigrees. (They may be the same species, but your average Chicago street pigeon has little in common with these birds that fanciers nickname “thoroughbreds of the sky.”) Breeders often acquire these birds at auctions. In most major pigeon races, including this convention race, the fastest birds are automatically brought to the block, where they can sell for upward of fifteen thousand dollars to become the progenitor for future generations of racers. These breeders are never allowed to fly free again, not only because of their value but because they’d fly back to the place where they were raised. Handlers, on the other hand, are the ones who feed, train, and raise the birds from when they are chicks; they are the “home” the birds fly back to.

For this convention race, all the handlers had to live near Chicago, but breeders from across the country sent in their infant birds to be raised by trusted handlers. Andy, who also is a breeder, was one of this race’s most sought-after handlers, having been sent ninety birds. But he told me he was feeling bad about his chances, as 15–20 mph winds from the south-southwest meant his birds would be fighting it all the way to his home.

Andy led me to his two lofts, which sat a few feet apart at the far end of his backyard. The grass bore a well-tamped path—a defined V—leading directly from the steps of his back porch to each of their entrances. These lofts, he told me, were where he spent most of his free time.

They looked nothing like the wire-meshed boxes I’d imagined. Instead, they were well-cleaned tan sheds with shingled roofs, windows, and ventilation systems. He explained, “If you don’t treat [the pigeons] right, they simply don’t come back.” One loft housed his breeders and was full of plump gray birds loudly flapping their wings and pecking at corn. The other loft sat empty. A few lonely shit stains were the only evidence of his ninety birds now somewhere between here and Coon Rapids.

Andy came to pigeon-racing as a child in Poland, which, then and now, is one of the world centers of the sport. He was introduced to it by a neighbor in his village. Andy still remembers meeting him and his birds for the first time: “He was sitting on a bench, rolling his cigarettes and smoking. He was throwing feed down on the floor, and the pigeons were coming down and eating. It was just very peaceful. He had time for everything.”

Soon after, Andy began to raise his own birds. But when he was eleven, the family moved to America, and he was forced to give them away. He later heard from his aunt back in Poland that some of them had escaped and found their way back to the now-empty farmhouse; there, they had babies and lived out their lives. “She couldn’t tell me because she knew I had the pigeon bug,” he said. “I’d feel sorry without being there and the birds are home.”

He spoke sadly about leaving the family farm. “It was not my choice to move to another country. I had to leave everything behind: my friends, my home, my birds,” he said. Having pigeons now, he said, allows him to hold onto that place. “I couldn’t imagine living somewhere without birds. There’s certain things that make you feel like, Oh, I’m home.”

***

Imagine being blindfolded and loaded in a car, then dropped nearly four hundred miles from your house in a random field in rural Iowa and trying to get home before dark. Oh, and not only do you not know you’re in Iowa, you don’t even know what Iowa is. That’s what these pigeons do.

What allows these birds, which were domesticated from rock doves (likely the type of dove that returns to Noah, olive branch in beak, in Genesis) more than five thousand years ago, to be able return to their homes from over a thousand miles away and from places they’ve never visited before remains a mystery. Scientists think they might navigate by using some combination of tracking the Earth’s magnetic fields with the iron in their ears and beaks, following low-frequency sounds, and recognizing visual landmarks and geography. A newer leading theory is that they create mental odor maps—linking specific scents with different directions that allow them to determine and return to their specific environment and its associated smell. Jon Hagstrum, a scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey who is a proponent of the sound theory, was previously quoted as being stunned by the lack of clarity on the topic: “I understand we don’t get dark matter or quantum mechanics, but bird [navigation]?”

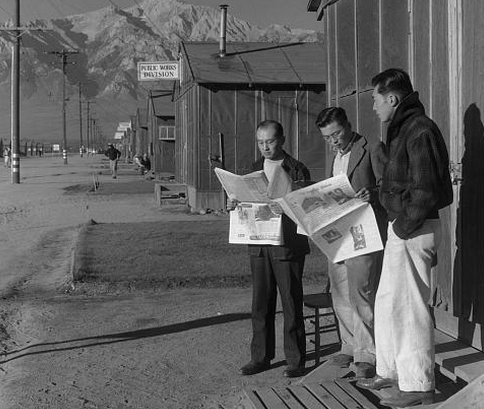

This homing ability has made pigeons valuable messengers dating back to antiquity, particularly during conflicts; pigeons have served on the battlefield from the Punic to the World Wars. (Perhaps the most famous is the First World War pigeon Cher Ami, who, despite losing an eye and leg from heavy German fire on the way, delivered a crucial message alerting American forces to the coordinates of an isolated and lost battalion.) And, for just as long as humans have used the birds as an aerial postal service, they’ve raced them. But it wasn’t formalized into a sport—with clubs and organized races—until Belgium went crazy for pigeons in the early nineteenth century. With railroads allowing for easy long-distance transport of the birds, and new, more accurate clock technology, miners and factory workers flocked to duivensport (literally “pigeon sport”) as an affordable alternative to horse racing. It slowly spread across Europe, especially in working-class communities from Liverpool, England, to Katowice, Poland, and then into America, brought mainly by immigrants carrying with them a vestige of home.

***

After Andy and I returned to the porch, the “nothing” I had heard about from Dave began in earnest. A few friends, a couple breeders who had sent Andy birds to raise, and some visiting fanciers from Belgium, who were smoking cigarettes out of packs adorned with images of deformed babies, had come over. Hornets made kamikaze dives into cans of Sprite while we sat around on the porch eating deep-dish pizzas and homemade sourdough and sipping Peronis. Andy milled around with a Grey Goose bottle filled with a drink he had concocted with vodka, honey, and lemon, and had us each take shots of it out of a shared glass.

While the tracker bands on the pigeons’ legs record and automatically upload the time of their return (because distances between lofts vary, scoring is calculated as yards per minute, not overall time) they have no GPS, meaning no one knows where they are. That transforms the race into one that exists almost entirely within your imagination. Have they been killed by a hawk? Run over by a car? Are they chilling in a barn, eating corn?

Calvin Gall, a fancier from Wisconsin and a friend of Andy’s, told me that the only clues are the scars the birds sometimes return with from their journeys. “I’ve seen pigeons come home with their legs broken [after] they hit wires. Their crop is ripped open,” he said. “How in the world did that pigeon keep coming home?”

As the clock ticked past 3 P.M., around when the first birds could feasibly arrive, everyone grew quiet, rising from their chairs to lean against the porch railing to stare at the cloud-speckled sky. Birds kept flying overhead. Everyone held their breath. Wild. My fellow porch dwellers kept coming over to me to whisper, “Just wait till you see them come home.” Sure, sure.

An hour later, Andy started getting a few beeps from the racing app on his phone, which notified him when pigeons entered competitor’s lofts. He had none yet. “I’m getting nervous,” he mumbled repeatedly, before going inside, fixing someone another drink, or bringing out more trays of food. “Do you need anything?” he asked every time he walked past, eyeing my empty plate.

While Andy was inside fixing a rum and Coke for a visiting Belgian fancier, someone screamed, “ANDYYYY! BIRDS!” Everyone’s eyes shot up to the sky as three pigeons flew over the top of the house. Andy leaped out the door and sprinted down to the lofts, repeating “Come, come, come, come!” and making a cooing whistle. The birds made sweeping circles over the house, seeming to revel in the cool wind rushing against their faces. Then one by one, they tucked their wings and fell in tighter circles, lower and lower, to the loft. They landed one after the other at the entrance, glanced side to side, and then hopped, as if it was nothing, back into their home. Everyone on the porch cheered wildly.

My heart was beating hard in my chest. The birds looked no different than all the others passing overhead, yet they had swooped down to us. It was as if nature, wildness itself, had decided it was tired of all that chaos. Couldn’t it find some peace—a home—in our human world?

By the end of race day, 603 of the 1,383 birds had completed the more-than-three-hundred-and-fifty-mile journey. Andy had forty out of ninety. Many would make it home come dawn, others were dead, and a few others were lost forever. Andy’s first three birds got fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth place overall, which was enough for a cut of the winnings. A great showing for a strong headwind, everyone reminded him.

The next night, the end of the convention was marked by a banquet at the hotel ballroom. I watched as donated birds were auctioned off, with Andy serving as the auctioneer, and as people were honored as ARPU Hall of Famers. While one fancier gave an acceptance speech, a waitress brought chicken soup to two Polish men at my table who asked, in near unison, “Bird?” To which the server replied, “Chicken soup, yes.” They shooed the bowls away in disgust.

In pigeon-racing, the first-place prize is split between the two people who helped shape the winning bird, who, for this race, were Tony Rossi, who bred the bird in Wisconsin, and Bozo Mladjenovic, who raised the bird just outside Chicago. Rossi told me, while people came over and slapped his back to offer congratulations, that he was shocked that Bozo had won, because he was a relatively unknown handler. He’d sent all but one of his birds to a more well-respected loft. In fact, the first bird Tony had sent to Bozo went missing–either killed or escaped. Bozo then drove an hour and a half to Tony’s home in Racine, Wisconsin, and asked for a new chick. When Bozo arrived, Tony says, he was distraught and was kept mentioning his daughter, who he said had died two years prior, at the age of only twenty-one. Tony added, “He could hardly talk. He was crying. I gave him [a replacement] entry.” Tony said he hadn’t heard from Bozo again until race day, when he got a call from him telling him their bird had won.

Bozo is a Bosnian immigrant who brought his love of the sport from his home country. His daughter Sofija had also loved pigeons since she was a child, and the two were partners, raising and racing them together. After she died of osteosarcoma, he kept her loft exactly as it was. “Her birds are in the loft, and that’s going to be forever here,” Bozo told me. “It’s here and it will always be here.”

He had only six birds in this race, a far cry from the larger-scale handlers like Andy, who had raced nearly a hundred. On the morning of the race, he said, his wife had prayed to Sofija for them to win. As the hours ticked ahead, they sat and waited anxiously at their kitchen table. His wife glanced at the clock. It was 1:11 P.M. His wife told Bozo that this number was a sign of an angel, that “our daughter [is telling] us something about today and it’s possible we can win.” And soon after, there it was: the winning bird, swooping in across the sky to come home to the loft. The parents wept.

But Bozo told me he isn’t happy yet. The bird, like all the winning ones in this race, are required to go up for auction in several weeks. Bozo said he would do anything, pay any amount of money, to make sure that the bird stayed with him. “We will celebrate after we make sure the bird is in our loft one hundred percent.” He doesn’t want it for breeding; he just wants, he said, to have the bird in Sofija’s loft “for the memories.” To know that bird was there with him, he would feel, his voice breaking, “So happy. So happy. So good.” Home again. Returned, against the odds, from the sky.

Oliver Egger is a writer, editor, and musician. His writing has appeared in The Believer, the Boston Globe, The Brooklyn Rail, and elsewhere.

Leave a Reply