Listen to the latest episode of the MindShift podcast to learn about how students are learning about the broader contributions of Asian Americans and their activism and what that means for civic engagement.

Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Ki Sung: Welcome to the MindShift Podcast where we explore the future of learning and how we raise our kids. I’m Ki Sung.

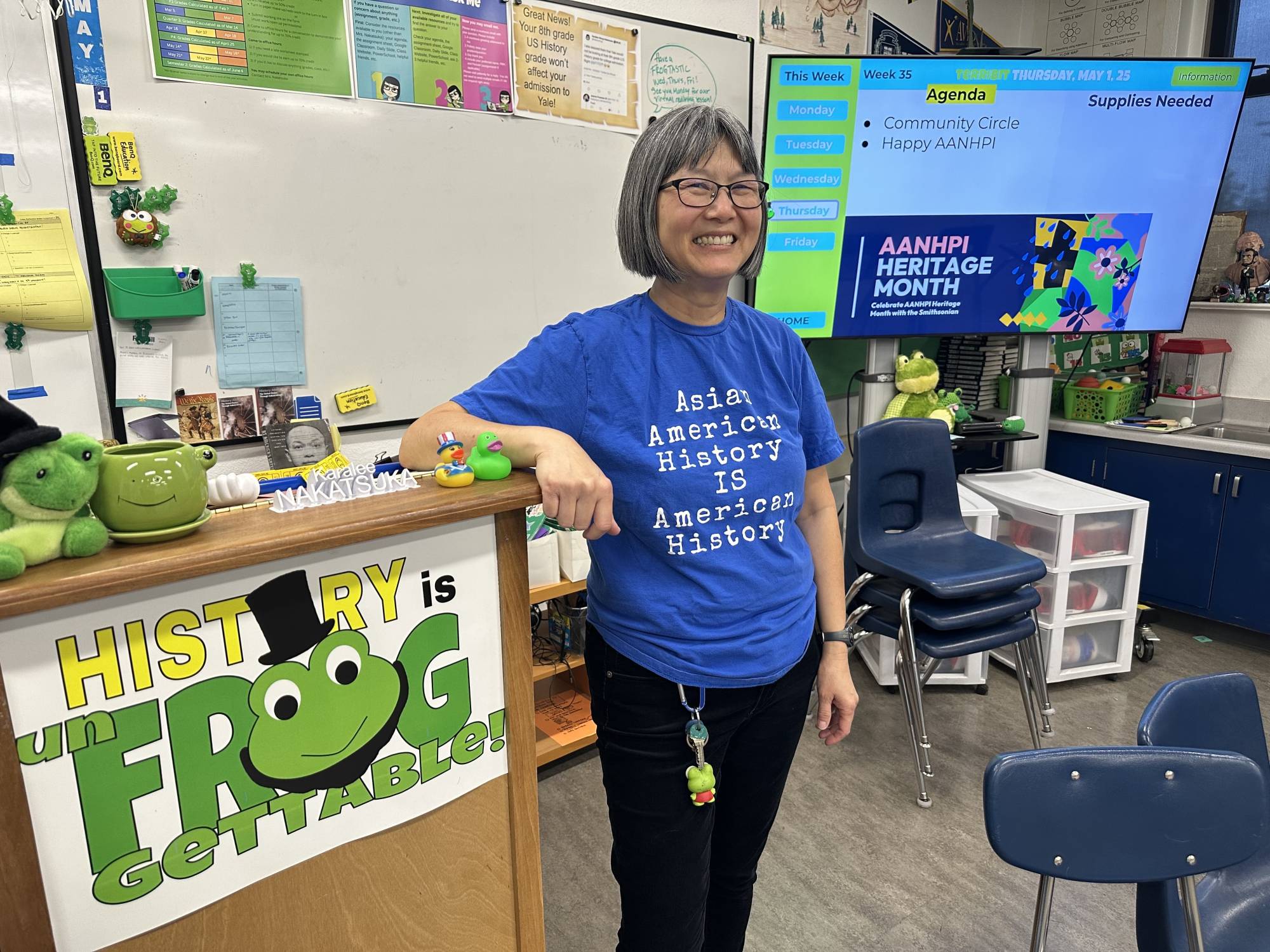

Ki Sung: Today, I want to take you to a middle school in a Los Angeles suburb so you can meet Karalee Wong Nakatsuka, an 8th grade history teacher at First Avenue Middle School. I visited back in May, which marked the beginning of a very special month.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Morning. Happy AANHPI Heritage Month. No Phones!

Ki Sung: Ms. Nakatsuka, greeting students at the door, was especially enthusiastic for Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Heritage month.

Ki Sung: I’ve known her for about a year now, and let me tell you she is very passionate about her work.

Karalee Nakatsuka:

So, we’re talking about citizenship and remember Joanne Furman says citizenship is about belonging.

Ki Sung: This lesson is about a Chinese American man named Wong Kim Ark. Before this year, most people hadn’t heard of him. But anyone born in the United States over the past 127 years – has him and the 14th amendment to thank for U.S. citizenship.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Wong Kim Ark was born of Chinese immigrants. And he says, I am an American, right? And they’re challenged, they test him whether or not he can be in America. And what do they say? They say no.

Ki Sung: Wong, with the support of the Chinese community in San Francisco, fought for HIS AND their right to citizenship.

Karalee Nakatsuka: But he challenges it, goes to the Supreme Court, and they say what? Yes, you are an American.

Ki Sung: But Asian Americans like Wong Kim Ark, and their activism, are rarely remembered. Students may spend a lot of time on social media, but he doesn’t pop up on anyone’s feed. I asked some of Karalee’s students about times they’ve discussed AAPI history outside of her class.

Student: I think in seventh grade I might have like heard the term once or twice,

Student: I never really like understood it. I think the first time I actually started learning about it was in Ms. Nakatsuka’s class.

Student: Like, we did Black history, obviously, and white history. And then also Native American.

Student: I think in Virginia when I grew up, I was surrounded by like an all white school and we did learn a lot about, like slavery and Black history but we never learned about anything like this.

Ki Sung: These students are surrounded by information because they have phones and have social media. But AAPI history? That’s a tougher subject to learn about. Even in their Asian American families.

Student: My parents immigrated here and I was born in India. I feel like overall, we just never really have the chance to talk about other races and AAPI history. We just are more secluded, so that’s why it was for me a big deal when we actually started learning about more.

Ki Sung: Coming up, what inspired one teacher to speak up about AAPI History. Stay with us.

Ki Sung: Karalee Nakatsuka has been teaching history since 1990, and brings her own personal history to the subject.

Karalee Nakatsuka:

Chinese exclusion is my jam, because when my grandfather came, he was a paper son.

Ki Sung: Meaning, he came to this country by asserting that he was a relative of someone already in the United States. Up until the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, specific immigrant groups weren’t targeted by exclusionary laws – anyone who showed up in this country just did so. But laws specifically excluding people of Chinese descent made impossible things like civic participation, justice, police protection, fair wages, home ownership. Adding to that, there were racist killings and calls for mass deportations all fanned by the media, pitting low wage workers against one another –

Karalee Nakatsuka: I, myself, because I didn’t understand history as well as I hope I understand it better now, like I’m talking with my students, like seeing the patterns, remembering– I mean, I’ve been teaching Chinese exclusion, I think probably from the beginning, but then connecting those lines and connecting to the present, that these view of the perpetual foreigners, view of yellow peril, these attitudes are still there and it’s really hard to shake.

Ki Sung: Despite her family history, Nakatsuka didn’t just learn how to teach AAPI history overnight. She didn’t instinctively know how to do this. It required professional development and a professional network – something she acquired only in recent years.

There are several programs throughout the country that will train teachers on certain eras of US history – the early colonial period, the American revolution, the civil rights movement. However…

Jane Hong: The reality is there’s very little training in Asian American history generally,

Ki Sung: That’s Jane Hong, a professor of history at Occidental College.

Jane Hong : When you get to Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander histories, there’s even less training and even fewer opportunities and resources I think, for teachers, especially teachers outside of Hawaii, kind of the West, you know.

Ki Sung: For context about her own school experience, Professor Hong grew up in a vibrant Asian American community on the East Coast

Jane Hong: I don’t think I learned any Asian American history.

Jane Hong: I did take AP US History. The AP US history exam does cover the kind of greatest hits version of Asian American history so the Chinese Exclusion Act Japanese American incarceration and that might be it right it’s really those two topics and then sometimes right the Spanish American War and so the US colonization of the Philippines but even those topics don’t go really deep.

Ki Sung: Last year, she hosted a two-week training for about 36 middle and high school teachers on how to teach AAPI history. It was held at Occidental College as a pilot program. So, Why did she develop this program?

Teachers, like students, benefit from having a facilitated experience when learning about any topic.

Ki Sung: In Hong’s training, teaching strategies are taught alongside history.

The teachers read books, visited historic sites and watched sections of documentary films, such as “Free Chol Soo Lee.” The documentary is about a wrongly convicted Korean American man whom police insisted was a Chinatown gang member in the 1970s. The documentary is also about the Asian American activism that helped eventually free him from prison.

Teacher Karalee Nakatsuka helped as a master teacher in Hong’s training. She realized she needed something like this after a pivotal year in the lives of so many: 2020.

Ki Sung: While the murder of George Floyd sparked a racial reckoning, AAPI hate was steeply rising. Asian Americans were blamed for COVID, Asian elders were pushed violently on sidewalks, sometimes to their death. Others onto subway tracks and killed.

Karalee Nakatsuka: My kids were, during the pandemic, someone yelled Wuhan at them when they were in the store with my husband, with their dad, and like, I thought we were in a very safe neighborhood.

Karalee Nakatsuka: And then, the Atlanta spa shootings happened.

Newsclip sound

Ki Sung: In March 2021, A white gunman killed 8 people, 6 of them women of Asian descent. Investigators said the killings weren’t racially motivated, but that’s not how Asian American women perceived it.

Karalee Nakatsuka: And across the country, all these teachers across, because I had met these really, really cool people important people, history people, civics people, and they reached out to me from across the country saying, are you okay? And I was like, “Oh, yeah, I’m okay. You should reach out to your other AAPI folks.” But then I was… I was like, I’m not okay.

Ki Sung: After a series of exchanges with professional friends, Karalee took action. She became more visible.

Karalee Nakatsuka: This is not normal Karalee. This is what Karalee normally does. But I felt so compelled to use my voice.

Ki Sung: She also became more outspoken about her experience. Like on the Let’s K12 Better Podcast with host Amber Coleman Mortley.

Amber Coleman Mortley: Does anyone else I just want to jump in on the question that I had posed or.

Karalee Nakatsuka: I’ll speak up. When you say empathy, that’s like one of my favorite words. And that’s huge because after Atlanta, people, it’s just all these wounds that we’ve had that have been festering that we don’t look at. I mean that as Asians, we are like taught, put your head down and just do everything and do it the best, do it better, because we always have to prove ourselves. And so we just live our lives and that’s just how it is. But we’ve been really introspective. And we’ve suffered microaggressions and harms and we just kind of keep on going. But after Atlanta, we’re like, maybe we need to speak up.

Ki Sung: And there was a letter written to colleagues – which a lot of Asian American women did at the time – in an attempt for understanding from their community.

Karalee Nakatsuka: …and I said, I just want to let you know what it’s like to be Asian- American during this time. And if I read that letter now, it feels very personal, it feels very raw and sharing just experiences of getting the wrong report card for my kid because they’re giving it to the Asian parent or my You know, different things, people mixing up Asian American people. So all those things came together to just make me feel like, hey, I need to respond. So also in my classroom, I said I need to, I need to teach anti-Asian hate. And these are all things that I don’t remember being formally taught.

Ki Sung: Karalee’s passion for AAPI history soon got an even bigger audience. She was already a Gilda Lehrman California history teacher of the year. But then she spoke out at more conferences and webinars and ran a professional community. She was featured in the New York Times and Time Magazine. She wrote a book called “Bringing History and Civics to Life,” which centers student empathy in lessons about people in American history.

Ki Sung: Back in her classroom, history from the 1800s feels contemporary.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Okay, so in the 1870s, what is the attitude towards the Chinese after the railroad is already built? They’re villains.

Karalee Nakatsuka: They’re villains. What else? They’re taking our jobs. They’re taking over our country. We don’t want them, right? And as a result of this anti-Chinese sentiment from across the country, they decide, okay, we’re going to exclude the Chinese. So 1882, Chinese Exclusion Act. All Chinese are excluded. But was the 14th Amendment still written in 1882? Yeah, it was written in 1868. So what do we do about that birthright citizenship thing? And they challenge it under Wong Kim Ark.

Ki Sung: The 1800s is relevant again because of the executive order signed by President Trump in his second term to redefine birthright citizenship. This executive order is making its way through the courts right now AND upends the 127-year old application of birthright citizenship as granting U.S. citizenship to individuals born within the United States.

Nakatsuka uses the news to make history more relatable through an exercise. She starts by showing slides and video clips to help explain the executive order.

Karalee Nakatsuka: On his first day in office, President Donald Trump sent an executive order to end universal birthright citizenship and limit it at birth to people with at least one parent who is a permanent resident or citizen.

Ki Sung: The president wants to grant citizenship based on the parents’ immigration status.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Trump’s move could upend a 120-year-old Supreme Court precedent.

Ki Sung: Nakasutka has the students apply the executive order to real or fictitious people.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Get out your post-it notes and look at what Trump is saying about who is allowed to be in America

Ki Sung: She then asks her students to write down those names, while she takes a poster and draws two columns: a “yes” column and a “no” column.

Karalee Nakatsuka: So if according to the Trump order, your person can be in America, that’s a yes

Ki Sung: Would that person be a citizen under the executive order? Or not.

Karalee Nakatsuka: And according to His executive order, your person would not be, they have to have one parent who’s a permanent resident or citizen.

Ki Sung: The students discuss among themselves the people they chose and what category they fall into. Then, while the students start putting their Post-it notes in the yes or no columns, Nakatsuka shares insights about herself about who in her family would be considered a citizen under the executive order.

Karalee Nakatsuka: So a lot of no’s are like my mom, like my mom wouldn’t have been able to be a citizen.

Does this order affect us? Yeah, it does. I mean it depends on people that you that you that you chose, right? so.

Trump, Trump’s birthright order, if it was back when my mom was being born, my all my uncles and aunties wouldn’t be here, then I wouldn’t be here if they weren’t allowed to be citizens.

Ki Sung: Nakatsuka reminds them about the central question in this activity.

Karalee Nakatsuka: You might know some friends, it might be your parents, right? And so that birthright citizen order is just like how we looked at the past. Who’s allowed to be here, who’s not allowed to be here? Who belongs in America, who is part of the we? Right?

Ki Sung: Some of the students’ post-its under the NOs, as in, no, they wouldn’t be citizens under the executive order are “mom,” “dad,” “My friends” and “Wong Kim Ark.”

At the root of this lesson in history, though, is a lesson students can apply every day.

Karalee Nakatsuka: Alright, so citizenship is about belonging. What kind of America do we want to be? And we’ve been talking about that from the beginning, right? In the beginning , who is the we?

Ki Sung: Learning about AAPI history has broader implications, Here’s professor Jane Hong again.

Jane Hong: Because of Asian American’s very specific history of being excluded from US citizenship, learning how much it took for folks to be able to engage kind of in the political process but also just in society more generally, knowing that history I would hope would inspire them to take advantage of the the rights and the privileges that they do have knowing how many people have fought and died for their right to do so like for me that that’s one of the most kind of weighty and important lessons of US history

Ki Sung: And this understanding isn’t just about AAPI history, but all American history.

Jane Hong: I think the more you understand about your own history and where you fit into kind of larger American society, the more likely it is that you will feel some kind of connection and desire to engage in like what you might call civic society.

Ki Sung: About a dozen states have requirements to make AAPI history part of the curriculum in K-12 schools. If you’re looking for ways to learn more about AAPI history, Jane Hong has a couple of resources for you.

Jane Hong: One docuseries that I always recommend is the Asian-Americans docuseries on PBS. It’s five episodes, covers a long expanse of Asian-American history.

Ki Sung: Her second resource recommendation?

Jane Hong: The AAPI multimedia textbook that’s published and being published by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. It is a massive enterprise with really dozens and dozens of historians, scholars from across the United States and the world. It’s peer reviewed, so everything that’s written by folks is peer reviewed by other experts in the field.

Ki Sung: For Jane and others committed to Asian American Pacific Islander history, the hope is that the complexity of American history is better understood.

Ki Sung: The MindShift team includes me, Ki Sung, Nimah Gobir, Marlena Jackson-Retondo and Marnette Federis. Our editor is Chris Hambrick. Seth Samuel is our sound designer. Jen Chien is our head of podcasts. Katie Sprenger is podcast operations manager and Ethan Toven Lindsey is our editor in chief. We receive additional support from Maha Sanad.

MindShift is supported in part by the generosity of the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation and members of KQED. This episode was made possible by the Stuart Foundation.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Leave a Reply