Apple TV+

Apple TV+Oscar-winner Steve McQueen’s latest film offers a new perspective on life in the capital during the devastating 1940-41 Nazi bombing campaign – dispelling myths and clichés.

“I can assure you, there is no panic, no fear, no despair in London town. There is nothing but determination, confidence and high courage among the people of Churchill’s island.”

So declares US war correspondent Quentin Reynolds in the British propaganda short London Can Take It, released in November 1940 as the Nazi bombing campaign over the UK, known as the blitz, entered its third relentless month. The film enshrined the idea of an indefatigable “blitz spirit” within the British people, a stoic yet cheerful defiance that paved the way for the ultimate defeat of fascism. The political and cultural value of this narrative has proved irresistible across the political divide. As writer and historian Angus Calder writes in his 1991 book The Myth of the Blitz, “the mythical events of 1940, would become subjects for historical nostalgia on the left as well as on the right”.

Apple TV+

Apple TV+The blitz has since developed into an integral part of the British national psyche, invoked at times of crisis and providing a vague but reassuringly familiar setting for episodes of Doctor Who or sitcoms like Dad’s Army (1968-1977) and Goodnight Sweetheart (1993-1999). When John Boorman dramatised his childhood in the blitz for the 1987 film Hope and Glory, he wrote in an introduction to his screenplay, “How wonderful was the war… All our uncertainties of identity, dislocations, could be submerged in the common good, in opposing Evil – in full-blown, brass band, spine tingling, lump-in-throat patriotism.”

The legend surrounding this chapter of British history often obscures the enormity of what happened in those dark months from September 1940 to May 1941, when more than 40,000 people were killed and millions more made homeless in towns and cities across the UK. The period is now being brought back into sharp focus by Oscar-winning artist and film-maker Sir Steve McQueen. His new film, Blitz, follows nine-year-old George (Elliott Heffernan) on an odyssey through a bombed-out London to find his mother Rita (Saoirse Ronan). His journey offers an unvarnished and startling glimpse into both the horror and humanity of the blitz.

The reality of the ‘blitz spirit’

Historian Joshua Levine, author of The Secret History of the Blitz, worked as McQueen’s historical advisor on the film. “People like to simplify the past to come to terms with it,” he tells the BBC. “The blitz served its purpose for the British nation at the time, it was co-opted as a propaganda instrument and for bringing the Americans on side, and an oversimplified story of the ‘blitz spirit’ took over. More recently, you had the reaction to that – ‘the blitz spirit was absolute nonsense, and people weren’t pulling together and it was shocking and everyone was misbehaving’ – and surely no one will be surprised that neither of those is wholly true. Sure, there’s an element of truth to both, but everything was much more nuanced, much more complicated, and so much more interesting.

“Steve McQueen is an artist, but he was really keen on getting it to feel right, and to look right. It’s quite a challenge to make a film look so extraordinary, at the same time as trying to keep it accurate, and he did.”

Despite McQueen’s emphasis on accuracy, the writer/director does not see his film as conscious effort to correct the historical record. “I’m not interested in correcting anything,” he told the BBC at the London Film Festival. “I’m an artist, I love to work on things that mean something to me. What was so interesting to me about this, the idea of this landscape, was that it was about a working-class family. This was a family drama, as well as a historical epic.”

Focusing on the communities of East London who bore the brunt of Hitler’s aerial onslaught, McQueen avoids the senior military and political figures who often take the spotlight in British war films. Single-mother Rita works in a munitions factory and volunteers overnight in a bomb shelter run by the remarkable real-life figure of Mickey Davies (Leigh Gill), an optician with a spinal defect who was elected chief marshal in the basement of the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange. While Churchill’s government dithers over an inadequate provision of shelters, it is these local community organisers who step in to support one another.

Alamy

Alamy“I’m interested in how, through these particular times, love can shine, basically. This is a picture about L-O-V-E, love. And it’s the only thing worth living for, the only thing worth dying for,” said McQueen “This [film] is not about anything other than looking at a particularly dark period in British history, but seeing the best of who we are. Because as much as we’ll be fighting enemies and fighting ourselves, the thing that champions all of that is love.”

This emphasis on community solidarity recalls wartime dramas like Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder’s Millions Like Us (1943), which explored the contribution of women to the war effort. It was well recognised at the time that the efforts and sacrifices of the working classes throughout the war should be rewarded with vast social and political change, leading to the 1942 Beveridge Report into social inequality and the post-war Labour government’s reforming agenda.

“Looking through letters in the national archives, you can find Lord Halifax (foreign secretary 1938-1940), who’s about as high Tory as it comes, writing that Britain was going to need a new society after the war based on fairness, and if he was saying it then attitudes really were shifting,” says Levine. “I don’t think people appreciate how much of a game-changer this period was. You had these situations where people found themselves bombed out of their homes, helpless and then being treated like gin-soaked, Dickensian beggars under a Victorian poor law, which treated poverty as a moral failing and required destitute people to approach various authorities and justify their need for humanitarian relief. Many of these same people were playing crucial roles in the war effort, and the government realised that the population couldn’t be treated that way. Wages rose, workers gained protections and surprising new attitudes arose. It was a kind of crucible for the welfare state, NHS and all that came afterwards.”

Highlighting home truths

While McQueen champions the human generosity found amidst the falling bombs, he doesn’t shy away from some darker truths. Stephen Graham and Kathy Burke play a menacing pair of racketeers who run an outfit stealing valuables from bomb sites. The extent of their depravity contrasts with the stereotype of the cheeky black-market spivs found in Dad’s Army or Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971).

But it wasn’t just criminality which threatened the wartime consensus. McQueen also explores the deeper social divisions of the time. George, the film’s young protagonist, is mixed-race, and his point-of-view offers an insight into the prejudices and assumptions of an imperial Britain. Along the way, he is taken into the care of Ife, a Nigerian air raid warden based on the real-life figure Ita Ekpenyon, whose experiences fighting xenophobia in bomb shelters were previously featured in the 2021 BBC documentary Blitz Spirit with Lucy Worsley. In this respect, Blitz works as an extension of McQueen’s 2020 anthology film series Small Axe, which explored episodes of black British history.

Alamy

AlamyThis shift in perspective represents a departure from typical depictions of 1940s Britain. “They’re boss films, you know, Passport to Pimlico (1949) and all that, they’re great films, but I’ve never seen that kid in any of [those] films,” Stephen Graham tells the BBC. “I’ve never seen a mixed-race child in a war film, set in the blitz, I’ve just never seen it.”

Indeed, the fact that wartime Britain, and more specifically London, was the metropole of a vast, global empire is often missing from contemporary discussions around World War Two. There is nothing anachronistic about McQueen’s diverse vision of London in this period, but nor is it entirely unprecedented. During the war itself, government propaganda was happy to emphasise that Britain had allies in the fight, and films like From the Four Corners (1941) and West Indies Calling (1943) explored the contribution of men and women who had come to the UK from across the British Commonwealth. It was only in the immediate post-war years that the popular understanding became so whitewashed. As film critic Raymond Durgant writes in his 1970 book A Mirror for England: British Movies from Austerity to Affluence, “The war against Nazism made race prejudice infra dig for a while”.

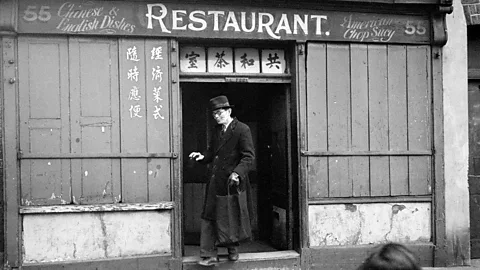

“For a start, there were pockets of London that were always diverse, particularly around the docks, and you would have black nightclubs, just as depicted in the film, and Chinatown, for example, was in Limehouse in this period,” says Levine. “Then throughout the war you also had people coming to help from all parts of the empire and dominions. There’s a brilliant story of a Jamaican airman, Billy Strachan, who sold his saxophone and bicycle to come here and join the RAF. Then also you had lots of refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe, so parts of Chiswick suddenly became Belgian, for example.

“London wasn’t the international city it later became, but on the other hand, there was a lot more diversity we’ve ever given it credit for, so I think this portrayal is really interesting and overdue.”

In focusing on characters and stories that have often been overlooked, Blitz cuts through decades of post-war nostalgia to bring the human experience of Nazi bombing to life. But this is not to say that the film is preoccupied simply with busting myths or debunking the patriotic narrative of the blitz spirit. Rather, McQueen digs deeper than the cliché to find the true breadth and complexity of life in the blitz, capturing both the enmity which drove people apart and the love which brought them together.

Alamy

Alamy“In the immediate aftermath of the war, the loudest voices were heard, and the official view – ‘Britain can take it’, cheerful firemen, everyone treading over broken glass shaking their fists at bloody Adolf – predominated. And then it was challenged, and there was a tendency in some circles to think that everything was terrible,” says Levine. “Now we’re at a point where living memory is turning to history, one thing we can do is take a broader view overall. We can accept that it was a time of near-unimaginable intensity, and people did things they had never done before. They behaved wonderfully well, they behaved shockingly badly, and many, we have to remember, did not survive the period. All these things can be true at once. The blitz was a messy thing, and I think maybe we’re now at a point where we can embrace the mess.”

Blitz is in select US and UK cinemas from 1 November and streaming on Apple TV+ from 22 November.

Leave a Reply